AUTHOR: AMR EL-TOHAMY

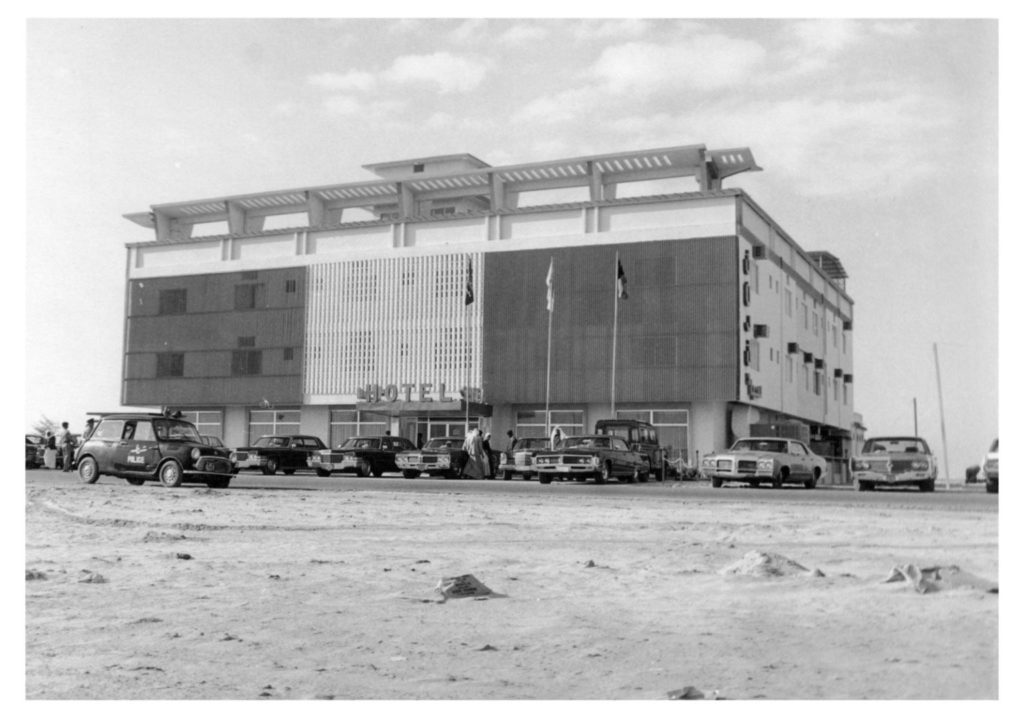

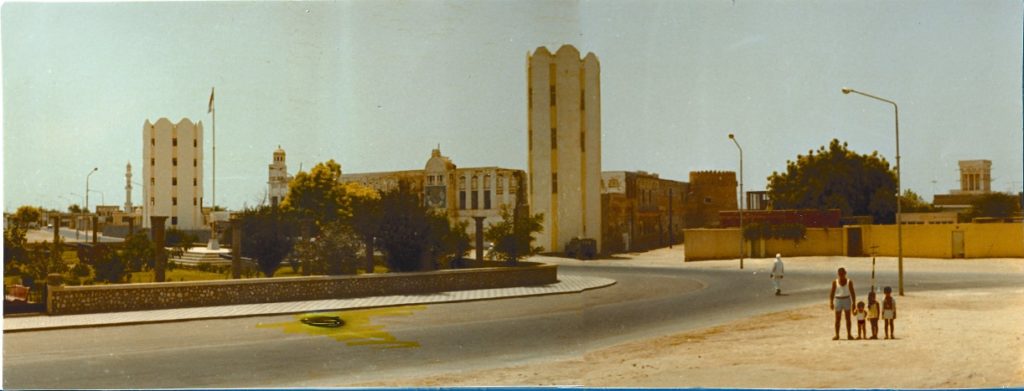

A new book titled “Building Sharjah” traces the architectural history of the city of Sharjah and the social and political contexts of its urbanization from the mid-20th century, from before the discovery of oil off its shores until the present day.

The book includes a large number of archival images that have not been published before and documents the urban features of Sharjah, which is the capital of the emirate of the same name and the third largest city in the United Arab Emirates.

The volume also includes architectural designs and plans that are published for the first time, obtained from city residents and the experts who contributed to its construction.

“Archiving buildings is part of archiving modern history,” Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi, founder of the Barjeel Art Foundation and a co-editor of the book, said in an interview via Zoom.

The book is an account of the story of the city and its residents, he added, “especially in light of the fact that the rising generation does not know anything about the history of the main landmarks of the city, some of which were demolished in the late 1990s.”

Al Qassemi explained that the book is not only about building a city, but about architecture as a construct of humankind, culture and urban renaissance.

Five researchers participated in the preparation of the book, conducting interviews, searching for architectural designers of buildings or their relatives, and searching in archives in the Arab world and beyond.

As for Al Qassemi, who was born in Sharjah, the book helped him to understand and assimilate his city more deeply, he said, and stirred within him a number of hypothetical questions about the possibility of the success of the Arab tide on the movement of culture and education in the city.

A Different View of the Gulf

The book was issued by the Swiss publishing house Birkhäuser, which specializes in urban studies.

It reveals the error of popular perceptions about the similarity of architecture in the Gulf countries, their primitiveness before the discovery of oil, and the inability to establish a distinct architectural style before their financial resources increased, according to Reem Khorshid, the lead researcher on the project.

Khorshid found a document in the British Library dating back to the 1960s, in the early days of oil exploration in the region, which shows that residents of the Gulf countries had already begun construction efforts and developing the educational infrastructure needed to achieve this.

Khorshid, who studied architecture at Cairo University, started working on this project in December 2017, conducting interviews with the designers of buildings, searching in archives to obtain accurate information and pictures of buildings, as well as analyzing and linking this information together.

The book records three periods of architectural identity of the city of Sharjah.

The first stage began during the presence of British forces in the city and reflects the architecture of the time. The second stage, after the discovery of oil, is the stage of modernity, which included the establishment of buildings of a modern nature faster through technology.

In the third and still continuing stage, which began in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the urban designs took on the character of the heritage of Islamic architectural identity.

The researchers also recorded another clear impact on the architectural identity of Sharjah, which is linked to the presence of large numbers of expatriates of different nationalities.

“These expatriates, who included engineers who worked in the city, also left touches related to their cultural backgrounds,” Khorshid said.

The book also records the impact of women on urbanization and the increase in production.

Al Qassemi said, “There is a whole generation of Sharjah women who played an influential role in building the city and its people through their work as teachers in schools, and the establishment of a number of associations such as the Sharjah Women’s Association and the Cooperative Society, which is the first cooperative society in the Emirates.”

One of the symbols of this generation is Al Qassemi’s own mother, born in the mid-1940s, who was one of the first teachers in the Emirates. He wrote a chapter in the book that reviews her educational journey and her role in encouraging many women to enroll in schools.

An Absence of Criticism

Some experts believe that documentary books about architecture play an important role in rooting societies in their past, but this does not cancel out the promotional role they play as well, especially if generous funding is available.

Nasser Rabbat, director of the Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, said that “Building Sharjah” joins a “trend that has its reasons for material abundance and knowledge orientation for development and sustainability, and to raise the sense of belonging among the Gulf people by linking them to their spatial history, while ignoring periods and stages that may not fit the picture presented today.”

Rabbat believes that the majority of studies concerned with documenting architecture in the Gulf need to add a critical perspective to the information collected in order to provide greater benefit to readers and not just “cold and neutral information.” He explained that “some studies neglect specific types of architecture that do not serve the promotional goal, such as the architecture of the nomads (Bedouins), and most importantly, the architecture of the workers recruited to the Gulf cities.”

Other researchers also call for more inclusive studies that have a greater critical dimension.

“Documentation is the first step towards understanding what is important, the ideas that have shaped the way we live today, and the way that we have lived in the past,” said Seif El Rashidi, an architectural historian and director of the Barakat Trust. But that should not be “only in the story of the greatest or most important buildings, but also in everyday buildings and places,” he added.

Al Qassemi agrees on the importance of documenting the architecture of workers, who played important role in building the society. Still, he believes in the importance of documenting any available resources for now.

“The absence of a significant archive in many Arab countries, and the difficulty of accessing the available ones, requires us to constantly strive to move towards archiving everything available for now.”

This article was originally published in Al Fanar Media on September 15, 2021. A screenshot of this article is available here.