AUTHOR: ANNA SEAMAN

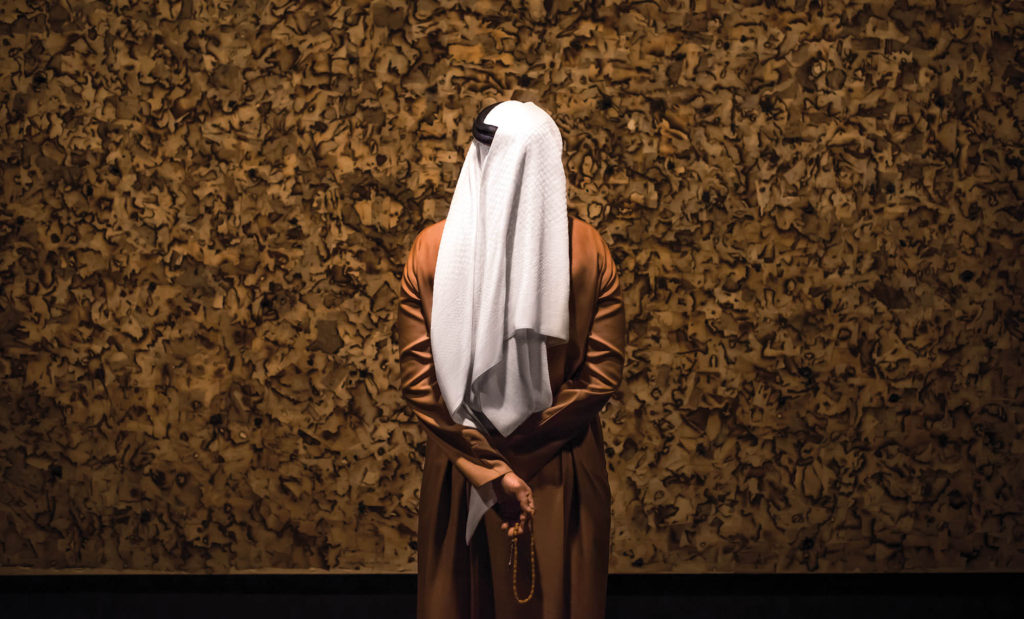

PHOTOGRAPHY BY RABEE YOUNES

Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi takes his collection on tour to change hearts and minds.

In January 2018, Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi, the founder of Sharjah’s Barjeel Art Foundation, announced he was putting Barjeel’s international and UAE activities on hold for two years. During that time, he has taken a series of teaching posts at some of America’s leading academic institutions and poured some of his seemingly inexhaustible energy into a forthcoming publication on Sharjah’s architecture. This month, Barjeel’s first exhibition in two years opens at New York University’s Grey Art Gallery. Taking Shape: Abstraction from the Arab World, 1950s–1980s traces the emergence and development of abstraction in the Arab region featuring nearly 90 works from the Barjeel collection. Here, we catch up with Al Qassemi to talk about the past 48 months as well as plans for the future.

ANNA SEAMAN: January 2020 marks the end of your two-year “warrior’s break”, during which you said you were planning to consolidate and take stock of the Barjeel Art Foundation’s activities, collection and exhibitions. What prompted this break?

SULTAN SOOUD AL QASSEMI: Between 2015 and 2018, we did so many shows that we almost suffered from burnout. So, when I saw an opportune time to pause, take a step back and look at everything that was happening, I took it. The good news is that we already had an exhibition cooking on the “cool fire,” so to speak, at New York University’s Grey Art Gallery, so that was slowly brewing. The break also allowed me to step back from Barjeel and from the family business and look at all this knowledge I had accumulated over the past decade and a half, which gave me time to propose a class to a number of US universities and pursue an academic career.

You have taken several teaching placements, the most recent of which was at Georgetown University in Washington, DC. What has been the most rewarding thing about teaching?

Yes, I taught at The Hagop Kevorkian Center at New York University, Yale University, Georgetown University, and [this month] I’m going to Boston College. The most rewarding thing for me, hands-down, has been the students. They are like an extension of my family. There’s a special relationship that forms when you teach, that can be like a peer relationship and, at a point, it almost becomes paternal, in the sense that you are invested in someone’s future. And then, in many cases these students become mentees, too.

What’s the most challenging thing about it?

Never to underestimate the students. They are more knowledgeable than one would think. It’s really important to stay up to speed on art and culture. I also sometimes find technology challenging. Many of these gadgets didn’t exist when I was at university, so I always go to my classroom at least an hour early, to make sure everything is working.

Does the course stay the same at each institution?

The title of the course is The Politics of Modern Middle Eastern Art and it’s an evolving course within the 13 modules. Sometimes I bring in foreign policy, or modules about graffiti or on Arab Spring art. And for Boston, I’ve included some modules on feminist artists as well as abstract art.

Is there a link between your teaching posts and the US tour? Why the US, why these cities, why now?

When I was teaching at NYU Kevorkian in spring 2017, Lynn Gumpert, the director of Grey Art, and I decided on a date for an exhibition. A few weeks later, she proposed the idea to do a show on abstraction. There have been a number of shows on modern art from the Middle East in the Arab world, but there’s never been an exhibition dedicated to pan-Arab abstraction. I should emphasise that whilst I was very open, it was Lynn’s initial idea. As for the touring part, there are five university museums in the tour. The Grey Art show obviously came about while I was a visiting faculty member at NYU. NYU also has an understanding with Northwestern University where they share exhibitions, so that was agreed as the next location. Another two university museums—Cornell and Boston College—were museums I visited personally and I went to see the directors, so these shows came upon my initiatives.

Why is a show of this magnitude so important for American audiences right now?

I have to say that it helps when the faculty or the director from an institution is familiar with the region, like Salah Hassan at Cornell, for instance, who was instrumental. I approached other universities in other parts of America who had zero faculty from the Islamic world and zero interest; there was complete rejection. This is really a reflection on how forward-thinking and progressive the institutions that are hosting the show are. Also, it’s important to note that we only work with university museums in America for two reasons. The first is that these are medium-sized museums and they’re much more malleable than larger institutions, which need years to put together an exhibition. The other aspect is the educational aspect—every single one of these museums will have symposia, conferences and talks, and they have the students involved, which is really important.

Educational programming and the dissemination of knowledge has always been a priority for you. Do you feel it has been successful towards changing perceptions or fighting stereotypes about Arab art and culture?

Changing is a huge word. I don’t want to say I’m changing perceptions, but I’m offering an opportunity for those who care to learn more. You can’t change somebody’s mind if it is set. If you tell someone the planet is round and they insist it is flat then there’s nothing you can do about it. Also, we should not neglect the region itself. A lot of people in the region don’t know about Arab art, so it has to be a two-pronged approach. As well as this tour, I’m really hoping that there are more opportunities for people to see art in the region, which, in many ways, is more important than the US.

Is this exhibition not coming back to the region?

Not in this iteration, no. But the works will be available. They will go to museums. In fact, many of the works are already reserved from January 2022. Also, by that point, I will want to work on a new project.

As Barjeel moves into its second decade and now that you’ve had a chance to take stock, how far do you think you’ve come with your achievements and how far do you think you’ve got to go?

I think we’ve made substantial progress, but when you start at a very low point even if you double or triple your numbers it’s still a very small number. We really need 100 institutions in the Arab world to do what Barjeel is doing and, in a region of 400 million people, having 100 public art collections is not many. I don’t want to say this, but no one else is pushing Arab art abroad. Take Mathaf [the Arab Museum of Modern Art in Doha] as an example. It has been there for as long as we have but they’ve only done one exhibition abroad. One. In a decade. I’m sure we can do better than that as a region. The only other major touring exhibition I can think of was the surrealism exhibition curated by Sam Bardouil and Till Fellrath, which began at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. That was purely Egyptian art, which was also great. But it can’t just be that. We need other collectors, other foundations, other institutions, especially ones backed by the state, to push this art internationally and go where art hasn’t gone before, which is everywhere really.

But, are you satisfied so far?

Yes, I’m satisfied. I’ve had so much fun, showing art and travelling with it. I think the fun aspect should not be underestimated. You feel like you’re a cultural agent, sending your representatives to Tehran, to Turkey, to Europe, or to America, Canada and Singapore. It is important that you reach out.

Recently, you have been vocal about the need for equality in art, and the show in the Sharjah Art Museum has been re-hung to address the balance between male and female artists. How easy was it to rise to your own challenge?

Well, I’m happy to say that it cost me a lot of money, which is a good thing and a bad thing. Out of the 120 works that were in the initial hang, only 20 remain. Sixty left to America, and we took out 40 works by men and added 40 new works by women. I took on the challenge of rehanging the exhibition with a 50:50 male-female balance without compromising on the quality. My first worry was wondering if I had done women a disservice because women did not have the same opportunities as their male counterparts. Is it fair to show five men and five women when only one of the women has been professionally trained? However, I must say that the quality of the women’s works is far superior to what some people think and the show looks very good.

So, do you think the problem was women not having been given the platform initially?

Yes. The women were not given a chance. Who controls the museum, who controls the funding? It’s majority men. Even if the head of a cultural authority is a woman, these are patriarchal societies and, in the end, the buck stops with a man. Men have to acknowledge that they are the reason that women have not been allowed to soar and to exhibit the way that their male counterparts have. What I would say is, there needs to be a radical solution for the under-representation of women in museums. Those radical solutions could include quota systems or, like the Baltimore Museum of Art [which] recently announced would only acquire works by women for one year. These are ways to redress the imbalance.

How do you personally feel when you visit an exhibition of works from your collection?

I recently returned to Sharjah after my teaching post in Georgetown and went to the art museum. I was amazed. Where else can you walk up and down and go from Morocco to Egypt, to Syria, to Iraq and to the Emirates and Saudi in one space? It’s just such a pleasure to see the cultural production from the past century. To me, it feels like I’m a gardener who’s been working on acquiring seeds, sand, soil and fertiliser and then moving seedlings around, tidying them up, planting them in the right season, watering them and patiently waiting. Now my garden has bloomed and it looks like Versailles. It is really beautiful and, in my opinion, it is not good enough that this is the only place where art from this region can be seen on such a large scale.

As if teaching and organising a traveling art show weren’t enough, you are working on publishing a book, Building Sharjah, in 2021 which tells the social history of the Emirate through the lens of architecture. What is it that particularly inspires you about architecture?

I’ve always loved architecture. Even the word Barjeel is an architectural word [it means wind tower] and I named my first company, a financial-services company, Barjeel in 2000. So, 20 years later and it’s still going strong. Architecture is definitely something I’ve always been interested in, even since I was a child. The book is about charting the history of some of the modern buildings of Sharjah that have been demolished and saving their place in the collective memory of the Emirate. I want to tell the story of Sharjah in the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s. You can tell the story through art, you can tell it through poetry, or newspapers, but you can also tell it through architecture.

What are your favourite buildings in the UAE?

Wow. Ok, I love the World Trade Centre in Dubai because of how environmentally friendly it is. And, even though I don’t like glass, I love Emirates Towers. In Sharjah, I love Bank Street. In Abu Dhabi, definitely the Al Ibrahimi Building on Electra Street and the old Adnoc building are two of my favourites.

What are your own earliest memories of Sharjah architecture?

I used to go to primary school in Choueifat and on the way to school, we would pass by a building called the Mothercat building in Al Wahda street. It was a beautiful super-modern building, surrounded by trees and in front of a large roundabout. It had a giant neon sign with a cat on it. It was demolished about 20 years ago and so, 30 years after my trips to school, I started asking questions about it and, years later, I found an image of it. It’s stunning; I can’t tell you how beautiful it is. It was all but forgotten, but now it will have a new life at least in documentation form.

You speak so passionately about Sharjah. Even though you now live in many cities around the world, will it always be home?

Always. Sharjah is with me everywhere I go. I am so attached to it that the idea of the Barjeel collection not being here is absurd. It’s not even something I would entertain. Even though I must say I’m disappointed that nobody has approached us to buy the collection. I mean, I would turn them down, of course. But I want them to want it. However, the only place that truly values this collection is Sharjah. The only place in the Middle East that will give me a space to showcase some of the best art from the Arab world is Sharjah. No other city would have given us a space this big, for this long. Only Sharjah.

You’ve described yourself before as an Arab nationalist. What do you mean by that?

What I have is an Arab nationalism for the 21st century. It’s not a re-creation of the Arab nationalism from the 20th century. It’s Arab nationalism for the modern age. This is a nationalism that acknowledges minorities, rather than try to suppress, ignore or neglect them. This is a nationalism that celebrates, rather than is antagonistic to, the other. This is a nationalism that is cultural, and not political. And this is a nationalism that is inclusive, not exclusive. Even non-Arabs can be part of this because it is a nationalism that includes those who are not ethnically Arab but culturally Arab. And that’s what we try to put forward through our exhibitions. I believe that we can’t move forward without acknowledging the mistakes of the past, and culture is a way for us to do that. This is a nationalism that is a positive force in the world.

This article was originally published in Hadara Magazine on December 1, 2019. A PDF version of this article is available for download here. A screenshot of this article can be downloaded here.