As Christie’s hosts London’s largest exhibition of modern and contemporary Arab art, we speak to the founder of the UAE-based Barjeel Art Foundation, whose unique collection is finding new audiences for Middle Eastern artists past and present.

Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi is scrolling through the photos on his phone to find a picture of a recent acquisition for the Barjeel Art Foundation. The painting is a perfectly constructed work by the veteran Lebanese artist Oumaya Alieh Soubra, made up of single blue brushstrokes.

Al Qassemi has just made the surprising revelation that one of his best sources of information about modern art in the Middle East is the general public. ‘It is true,’ he says. ‘I had never heard of this artist until a member of the public mentioned that she was missing from our collection.’

As unexpected as this may sound given his standing as an authority on the subject, Al Qassemi is keenly aware of how little has been written about the history of modern art from the Arab world.

‘There is an urgency in documenting the voices and first-hand accounts of artists who were active in the mid-20th century,’ he says. ‘We need to write down their histories before they are lost.’

As the founder of the Barjeel Art Foundation, Al Qassemi is committed to promoting art from the region. ‘My aim is that one day Arab art will be taught on a par with other art histories in universities across the world,’ he says.

This is not a pipe dream. Since he established the foundation in 2010, Al Qassemi has been in demand as a lecturer, teaching courses on Middle Eastern art at Yale, Harvard and Boston College in the United States, and Sciences Po in Paris.

Born in 1978, Al Qassemi is a columnist and researcher on social, political and cultural affairs in the Arab world alongside his work with the foundation. After studying in France, he came to prominence for his commentary on Twitter during the Arab Spring, helping to make sense of the seismic events happening across the region.

These days, his Twitter feed is a mixture of politics and art — you’re just as likely to find a link to a feature he’s written on the crisis in Sudan as a plea for information about a missing painting by Samia Halaby.

‘There is still so much scholarship to be done,’ he says, ‘There needs to be a lot more cross-cultural dialogue within the Arab world. I feel like we still don’t know each other as well as we could.’

It took time to develop a collecting strategy for the foundation: ‘Initially you could say I was buying whimsically,’ he says. However, as the foundation grew and generated interest, Al Qassemi realised he had a duty to ensure that the collection had an identity.

‘I see myself as a custodian,’ he says. ‘I’ve modified my interests to suit the uniqueness of the foundation.’ He describes the collection as ‘rooted in Modernism’, ‘somewhat political’, and ‘shining a light on women and minority artists’.

‘We have work from various ethnic, linguistic and religious backgrounds,’ he says, ‘by artists of Arab, Amazigh [Berber], Armenian, Circassian, Jewish and Turkish descent.’

Al Qassemi takes inspiration from Eduardo Costantini, the Argentinian businessman who established MALBA, the Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires. ‘Costantini has a saying: “a private collection for the public good”. That is how I see Barjeel.’

Research is a key part of the foundation’s remit. ‘There is a lot of fraudulent activity out there,’ says Al Qassemi. ‘Many Arab Modernists have been faked. It is important that our paintings are exhibited and scrutinised so that scholars have something genuine to study.’

To this end, the foundation actively loans out artworks to exhibitions worldwide — most recently, a series of vibrant canvases by Mohamed Melehi to Tate St Ives in the UK for its retrospective of Morocco’s 1960s Casablanca Art School.

Today, Al Qassemi is at Christie’s to oversee the installation of Kawkaba: Highlights from the Barjeel Art Foundation, which forms part of Modern and Contemporary Art of the Arab World, the largest show of art from the region exhibited in London.

Curated by Dr Ridha Moumni, Deputy Chairman of Christie’s Middle East and North Africa, the exhibition evades the regionalist trap by employing an open brief: the title Kawkaba means ‘constellation’, reflecting the myriad artists based in the region.

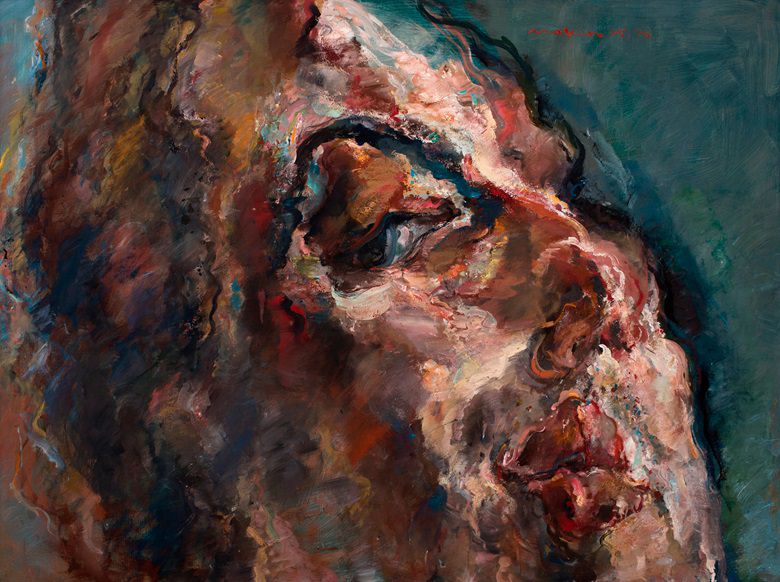

Much of the artwork on display challenges stereotypes, says Al Qassemi: ‘There is this idea that all art from the Arab world must be abstract or non-objective, but this could not be further from the truth. The show includes landscapes, city scenes, portraits of labourers, fighters and prisoners, as well as domestic scenes.’

Visitors may also be surprised to see depictions of space travel, scientific discovery and technological progress.

There is a focus, too, on artists who were committed to forging new cultural identities — figures such as Kadhim Hayder, who established the Bagdad Modern Art Group, or the Sudanese painter Kamala Ibrahim Ishaq, founder of the groundbreaking Crystalist group.

There are paintings by Shakir Hassan Al Said, the pioneering Modernist who developed a complex aesthetic based on the existentialist concept of temporality, as promoted by the philosopher Martin Heidegger; and there are works by the Surrealist Inji Efflatoun, who was jailed in Egypt for her Marxist beliefs in 1959.

The show is highly political — how could it not be, in a region that has experienced colonialism, struggles for independence and civil wars? There are artworks that address the Algerian War of Independence, the shifting power structures in Iran, and the Lebanese Civil War, as well as women’s liberation movements and the tensions between religion and secularism.

However, Al Qassemi is keen to point out that the region’s political history is just one of many sources of inspiration for artists: ‘Sure, there are political undertones, usually because of the specific circumstances of the artist — they could be a refugee or may have grown up during the colonial era — but you will find just as many works inspired by Islamic, Coptic or Judaic traditions.’

As a student of political history, Al Qassemi admits he sees politics everywhere: ‘Modernity in the Arab world is very much entwined with its political history, particularly when considering the rights of women. In an era where their rights were denied, they found their voice through music, poetry and art.’

Yet he is a great believer in the transformational power of culture during times of volatility. ‘It is good to be associated with art and beauty,’ he says. ‘It is important to focus on the positive aspects of our cultures, not for the outside world, but for those of us living through it.’

Kawkaba: Highlights from the Barjeel Art Foundation runs until until 23 August 2023. Held in partnership with the Barjeel Art Foundation, it is part of the exhibition Modern and Contemporary Art of the Arab World at Christie’s in London.

This article was originally published in Christie’s on August 3, 2023. A screenshot of the original article can be downloaded here.