ARTICLE BY PAUL LASTER

What happens when human studies lead the soul of a natural born art collector? We asked Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi.

An avid art collector, Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi is an Emirati columnist and researcher on social, political and cultural affairs in the Arab Gulf States. Founder of Barjeel Art Foundation, which is located in Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates and focuses on modern and contemporary art from the Arab world, Al Qassemi was a practitioner-in-residence at the Hagop Kevorkian Center of Near East Studies at New York University in 2017, a 2018 Yale Greenberg World Fellow and lecturer at the Council of Middle East Studies in Yale University, an Adjunct Instructor at the Center of Contemporary Arab Studies at Georgetown University in 2019, and is currently teaching a cou-0rse on “Politics of Modern Middle Eastern Art” at Boston College while conducting research for a book that documents the modern architecture of Sharjah. Conceptual Fine Arts recently spoke with Al Qassemi in Boston to discuss his vast collection of Arab modern art, a part of which is accessible in a travelling exhibition, “Taking Shape: Abstraction from the Arab World, 1950s-1980s” that’s on view at the Grey Art Gallery, New York University, through April 4, 2020.

Do you come from a family of art collectors?

Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi: My extended family includes a number of collectors, most notably the ruler of Sharjah, but not my immediate family.

What was the first piece of art that you acquired?

Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi: The first piece of art that I acquired was in 2002 and it was a painting of a door by the Dubai-based Emirati artist Abdul Qader Al Rais.

Why did you establish the Barjeel Art Foundation?

Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi: I started Barjeel because I was collecting for a number of years—between 2002 and 2008—and people were asking me about the works I was buying and where they could see them. I realised that there was no place to showcase works, so I wrote letters to the government of Sharjah in 2008 asking them for a space. In 2009 I was given the space in a beautiful building that they were renovating in the Al Qasba district of Sharjah.

What led you to focus the foundation’s collection specifically on Arab artists?

Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi: I was initially buying artists’ works from South Asia, Iran, Turkey and the Arab world. I was looking at the so-called MENASA region and I found that there were many collectors from Iran buying Iranian art, Iraqis buying Iraqi art, Egyptians buying Egyptian art and many South Asians buying South Asian art, but there weren’t enough collectors looking at the region as a whole. I decided to concentrate on the region because I felt it was a way of telling a story of the region. There is an argument towards including Turkey, Iran and parts of Africa in the collection, but I had budgetary constraints, so I decided to focus mainly on art from the Arab world. Also, I’m very much a Pan-Arabist at heart. I believe in Pan-Arabism culturally and economically, but not political Pan-Arabism.

Do the artists have to be Muslims?

Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi: No, not at all. One of the delights of collecting art from the Arab world is rediscovering the ethnic groups that continue to exist in the Arab world, whether they are Christian, Jews or Bahá’ís. We almost always make sure to include different ethnic groups in our exhibitions. The exhibition in New York has work by the Jewish-Egyptian artist Ezekiel Baroukh, the Armenian-Lebanese artist Seta Manoukian, Bahá’í-Palestinian artist Meliheh Afnan and Mohammed Khadda, a Berber artist from North Africa. I always make sure to look at ethnic groups within the Arab world. This is not an ethnic Arab collection. It’s a collection of art coming from the Arab states—not just art by Arabs. There are many people who live in the Arab world that are not ethnically Arab. We always try to emphasise that many artists are North Africans of different ethnic groups or that they are from the Lebanon, Turkey, Iraq and even Dubai. We have artists who were born in Iran that have been very active in the UAE, like Hassan Sharif. Some of these artists are not ethnically Arab artists, but politically they come from Arab states.

Are there Arab artists from the diaspora in the collection?

Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi: Yes, there are plenty. When does someone become diaspora? We have Dia al-Azzawi artworks pre-1976 that were created in Iraq. After 1977 he becomes a diasporic artist. We have works from his time in Iraq and his time outside of Iraq, when he was in Europe. We very much like to look at Arab diasporic artists. I think it’s important to tell the story of the migration of these artist, as well.

Is the focus of the collection more on modernist practitioners or does it extend to recent works by contemporary artists?

Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi: Initially, I was almost exclusively buying contemporary art, but then I realised modern art appealed more to me. One of the things that changed my being just like any other collector—someone whose taste evolved over time—is that I realised that my love was mostly for modern works. The collection went from being heavily contemporary with a concentration on modern to vice versa, from heavily modern with a concentration on contemporary art. The same thing with women artists. For example, over the past decade I’ve really doubled efforts to buy works by women artists, which I felt were not missing but not fully represented in the collection. This is part of my evolution as a collector. (In this regards we recommend you to read our interview with Valeria Napoleone, who is dedicating her entire art collection to female artists)

How far and wide do you search for works to add to the collection?

Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi: I travel to North America. I go to Europe. I go across the Arab world—from the Gulf to Morocco. I like to go to Lebanon, Jordan, Egypt, Libya, Tunisia and Algeria. I look at private collections. I look at auctions. I look for any possible way of getting works. Sometimes it takes years to acquire an artwork. You have to cultivate a relationship with the owners of the work. Then they decide—sometimes many years later—to sell the work.

Do you work with specific dealers and specialists in the field who find works for you to acquire?

Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi: I’m actually open to anyway whatsoever to find important works. Lately I’ve been using social media to put out calls asking people about certain artists and I get connected to these artists’ families or their descendants. I’ve been using Facebook, Twitter and Instagram to find modern artists from the Arab world.

What are some of the most coveted pieces that you’ve acquired for the collection?

Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi: It’s very difficult to pick specific works, but definitely The Last Sound by Ibrahim El-Salahi is a favorite. It was acquired through Meem Gallery, which you probably know. And recently in Jordan I got a work by Suha Shoman called Mystical Chants. I had been looking for a piece by her for a long time. These are just a couple of my prize works. As I said, it’s very difficult to play favourites.

Does it matter if the artist is self-taught or college educated?

Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi: No, not really. Some of the works we acquired are by artists before they were trained. And we have, as you know from your recent research, many self-taught artists, such as Baya, an Algerian painter who was admired by the Surrealists. And there are so many others.

Do you see the modernist and contemporary art influences coming from the West—from Europe and the United States—or have some of the regional artists also been influential on following generations?

Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi: I believe that artists from the Middle East, North Africa and the Arab world have multiple influences. Many of them look at traditional crafts, some of them look at Islamic art, some look at Coptic art, while a number of the others are influenced by Western artists. So it’s quite a mixed bag of influences and traditions that these artists are looking at and considering. It’s not a single source of influence.

What role did the fine art societies in countries like Bahrain, Kuwait and the UAE have in shaping the Gulf region’s art scene?

Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi: I think one of the most prominent fine art societies is the one in Kuwait, although there are others, like you said in Bahrain and the UAE. The Emirates Fine Arts Society was founded in Sharjah in 1980, while the one in Kuwait was founded earlier, in the 1950s or ‘60s. These are really sites of interaction, that not only included artists but assorted intellectuals, journalists, poets and playwrights. People from different intellectual backgrounds would come and exchange ideas and that was instrumental in forming a modern art identity. Let’s say an archaeologist would explain a recent find. These motifs would work their way into artworks. Dia al-Azzawi’s work was influenced in this way, but also others. The art societies were also spaces of social activism. They were seen as benign by the governments of the Gulf they were seen as not really harmful, because they were working under the umbrella of art. You had a lot of interaction between the intellectuals away from the usual government censorship, which you wouldn’t have in the journalists’ union, per se, or any other union.

Was there a noticeable change in the way that the regional artists worked when colonialism came to an end?

Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi: Certainly, across the Arab world you could almost see the difference between pre- and post-colonial art. For instance, as soon as the colonial period ended in Tunisia the artist Safia Farhat, introduced ideas that were banned during the colonial era, such as working with crafts, doing tapestry, using traditional materials like burlap and other items that really weren’t allowed during the colonial era. The same thing was true of Morocco. (Here is a link to our paper about the use of traditional techniques in European contemporary art)

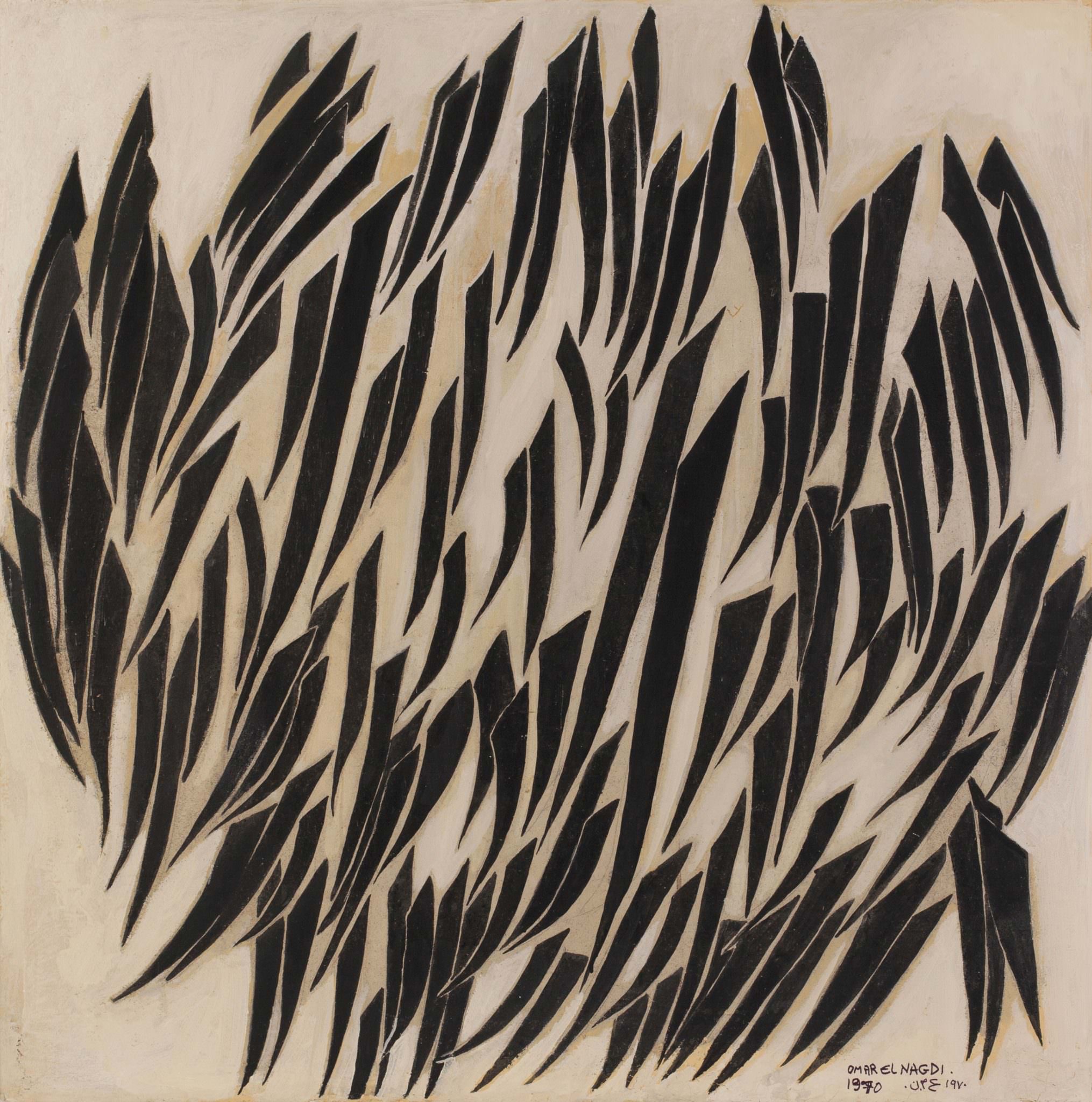

Why did you decide to solely focus on abstract Arab art from the collection for the traveling show, which is currently at the Grey Art Gallery?

Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi: The credit for this focus goes to Lynn Gumpert, the director of the Grey Art Gallery. It was very much her idea and it turned out that there had never been an exhibition or a book focused on this subject in the West. There had been an exhibition on Arab abstraction in Kuwait, but that show didn’t have a catalogue. There was never an exhibition of this kind anywhere outside of the Arab world on abstraction. It was important to set the record straight on where Arab abstraction came from, what were its influences. And I cannot emphasise enough the importance of having a book on it with essays by eight of the great living scholars on Arab art. It finally brings their ideas and thoughts together. As someone who teaches in the university I never had a text to assign to students and now I have eight essays, which I can share with them to learn about the origins of Arab abstraction.

What point of view are the curators, Lynn Gumpert and Suheyla Takesh, curator at the Barjeel Art Foundation, aiming to present in the selection of abstract works on view?

Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi: I can’t speak on their behalf, but I can say that I believe they wanted to show the multiple influences rather than a single influence or the influence of the Casablanca School, the influence of the Khartoum School, the Baghdad School—showing how these abstract artworks developed in the Arab world. I’m almost as intrigued by their selection as you are. I never get involved in curating. They had to select from works from what I had bought over the past 15 years. I admire that they were able to put together this show, especially considering the constraint that they had working with a single collection.

How does this show differ from the presentation that you have had on view at the Sharjah Art Museum for the past few years or from the Whitechapel Gallery exhibitions in 2015 and 2016?

Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi: The Whitechapel exhibition was almost encyclopedic from the collection. It was an exhibition that spanned a century and included figurative works, landscapes, abstract, video, photography and conceptual art. It was encyclopedic of the collection, but not encyclopedic of the Arab world. The exhibition in Sharjah is just highlights from the collection. It includes works in different mediums, but mostly from the modern era. I think that out of 130 works 127 are modern works and the others are contemporary works by artists like Mona Hatoum and Etel Adnan.

How has the scope of the collection and your thoughts on Arab modern and contemporary art evolved since you founded the Barjeel Art Foundation in 2010?

Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi: Oh, it has evolved heavily. I wish that I knew what I know today 10 years ago, because many of the works that I’m looking for now were more readily available. They were accessible at auction and the prices were affordable, for me at least. Now, the more I know the more I wish that I had known this information earlier. I’m sure the same thing will happen in 2030. I’ll probably wish that I had known in 2020 what I’ll know in the future, because these works are so rare to come by. I’ve definitely evolved. There are many works by female artists that are nearly impossible to come by now. I’m struggling to find their works. For example, modernists like Naziha Selim, even though we have two of her paintings, there were larger works available for a fraction of the price at an earlier time.

What do you hope the takeaway will be from audiences viewing the collection during its American tour, which already has five venues?

Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi: I always say that this collection is available for people who are ready to change their minds and change their knowledge of the Arab world. This is an opportunity. I’m looking to attract new visitors, which is always wonderful, but I think people have to approach this exhibition with an open mind. I must say that I’m almost as excited about the book as I am about the show, because it’s a lasting document and such an important edition to the libraries of the world. It’s important to have so many texts about Arab abstraction, which includes essays on works that are not even in the collection. The book is actually more expansive that the collection.

I am looking forward to the collection going to Michigan, for example, because it’s a place where many Arab Americans traditionally live. I’m interested in seeing the reaction there. Chicago—or at least The Block Museum of Art at Northwestern University in Evanston—has a completely different vibe than New York, and the same is true of Boston. Obviously with the Johnson Museum of Art in Cornell, you have Cornell being an important center for the study of African art. Each one of these venues comes with a different focus.

This article was originally published in Conceptual Fine Arts on March 12, 2020. A screenshot of this article can be downloaded here.