AUTHOR: ALISON TAHMIZIAN MEUSE

A daring Gulf Arab commentator goes West, leaving behind his thought-provoking collection of modern Arab art for the public to contemplate.

Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi — the Twitter giant, champion of modern Arab art, and beloved host — has left the UAE after two decades.

This infectious personality, who rose to prominence with the 2011 Arab uprisings for his daring political and social commentary, last year took a hiatus from social media. The Gulf crisis had reverberated back home, and new cyber-crime laws meant enormous scrutiny on any public statements.

“Things are so tense in the Gulf that I feel if I wrote an article calling for legalizing prostitution, gay rights, atheism, marijuana, civil marriages, gambling, press freedom, releasing political prisoners, constitutional democracy and the abolition of capital punishment no one would bat an eye,” he posted to Facebook in June 2017, days before his profiles turned static.

With newfound time — and sanity — on his hands, Al Qassemi shifted his focus to establishing a long-term home for his art collection, staking out the narrative on modern Arab art, and planning his next life move.

It was during this year of evolution that I got to know Al Qassemi.

For even as he kept a low profile online, offline his famed majlis (or salon) remained a creative crossroads, his villas bearing witness to thousands of personalities passing through their gardens, art-filled rooms and dinner tables.

An invitation to Al Qassemi’s majlis was an invitation to a creative ecosystem, a place where connections were established and nourished, where acrobats met architects, where bankers broke bread with leftists. A mecca for all the people who painted the canvas of Al Qassemi’s Dubai.

And for the guests who participated in his majlis over the past two decades, his departure leaves a hole where a small nerve center once was.

Mumbai to Dubai

Al Qassemi was born on January 1, 1978 in Dubai’s neighboring emirate of Sharjah, at a time when he remembers there was “no such thing as traffic” in the UAE, now a global crossroads.

His first window to the world was in the early nineties, when his Kuwaiti cousins — fleeing invasion by Saddam Hussein’s forces — came to stay with his family. “Before then, I didn’t know what a refugee was,” he said, sitting behind his desk in his breezy Sharjah office on a July afternoon.

To his right is a photo of his late father, talking on a beige landline — not unlike the one that sits on Al Qassemi’s desk.

His mother, he says, was among a group of 10 women that in 1977 founded the UAE’s first co-op. “I wanted a picture and I finally found one,” he says, pulling up a black-and-white photo of the storefront on his phone.

The office feels kept up, but not updated. It is evidence of the UAE’s not-so-distant past that Al Qassemi so cherishes. The dated surroundings are juxtaposed — fittingly — by Al Qassemi’s modern art.

Behind him is a massive sepia tableau of Star Wars-esque battle droids loitering around a run-down city, leaning against an abandoned muscle car.

Before him, a potted cactus — a gift from his childhood nanny before he left the country.

His cabinet is stacked with old photo albums. In one photo, Al Qassemi stands smiling in front of the Mumbai gate on his first business trip to India.

Barjeel Holdings, he explains, was the first brokerage to sell foreign stocks in the United Arab Emirates. It attracted and maintains an almost entirely Indian clientele.

“We have 40,000 clients, and all but a few dozen are Indians,” he said.

A list of rules on the wall, including “No hedge funds, No structured funds” followed by “No funds period”, are what shepherded the company through the global economic crisis.

Barjeel was the source of wealth that allowed Al Qassemi to become a serious art collector. In 2010 he launched the Barjeel Art Foundation, making it his mission to hunt down the most consequential works of modern and contemporary Arab artists — whether at the home of a speculative Hong Kong collector or in the obscure online sales of America.

Paris awakening

Al Qassemi got in touch with his Arab heritage not in the Gulf, but as a student in Paris.

His newfound appreciation of the language and culture came through evenings spent with his Emirati roommates in Paris, listening to Umm Kalthoum, reading Arabic literature and visits to the Institut du Monde Arabe.

In an essay, 13 Degrees East, he recalls dragging a satellite dish down the streets of the French capital to capture the Arab satellite channels, pointing it, on the advice of a salesman to 13 degrees.

It was an awakening that never stopped, and he has since made it his mission to share with his fellow citizens in the Arab world — and the entire world for that matter — the region’s modern history.

On a July afternoon, Al Qassemi led the way down the breezy stairwell from his Sharjah office building to the street. He can count on one hand the number of times he’s taken the elevator.

A short drive leads to Sharjah Art Museum, the new home of the Barjeel collection.

More than 100 paintings and sculptures will be on display for a period of five years.

The loan, Al Qassemi hopes, will be extended. It is a hint that the daring commentator, a rarity in the image-obsessed Gulf, may not be coming back to live in the Emirates anytime soon.

In the Barjeel wing, he takes in a map of the world that shows the arc of the collection’s journey, from exhibitions in North America and Europe, then east to Korea and Japan.

Barjeel even brought its message to Tehran in 2016, the first exhibition of modern Arab art in Iran — a rival, though important trading partner, of the UAE.

Al Qassemi reflects that most Iranian attendees had no idea that the Arab world had produced such a body of modern art.

By art world standards, what Barjeel has done in the past 10 years is staggering. Karim Sultan, the director and one of the curators of Barjeel, says the norm is for a collection to exhibit once every year or two. Barjeel has done multiple exhibitions and loans each year it has been in existence.

The Sharjah exhibit is a sort of homecoming.

Staking out history

Barjeel is not simply looking to put Arab art on the map. It is looking to establish the narrative of 20th century Arab art before Western institutions do it on the region’s behalf.

“We’re at a very precarious moment,” said director Sultan. “Things are being written, exhibitions are being planned and courses are being developed about art in the Arab world.”

When the collection first started in 2010, Al Qassemi and his team quickly realized there was a major knowledge gap when it came to 20th century Arab art, an era which spanned the fall of monarchies and colonial overlords, the percolation of new political movements and ideas, and the rise of new authoritarian regimes.

The region’s modern art history “hasn’t been written or codified yet — particularly in English,” said Sultan. He points out that many people know Umm Kalthoum, the Egyptian singer. They know Naguib Mahfouz, the writer.

But how many people can name an Arab artist?

With Al Qassemi at the helm, Barjeel over the past decade grew its collection to approximately 1,000 works and worked feverishly to put them on the map and explain their significance and place in a global conversation.

That means exhibitions near and far, networking with curators and educators and now, leaving the collection to the public.

“It’s never been done before in the Arab world, where a private collection is being gifted to the public free of charge,” Al Qassemi said.

“They’re very important paintings. They should be out there,” he stresses, with urgency and a sense of mission in his voice.

The tour

A walk through the Barjeel collection in Sharjah reveals a constellation of messages, echoes and themes that holds the observer’s attention through the entire exhibit.

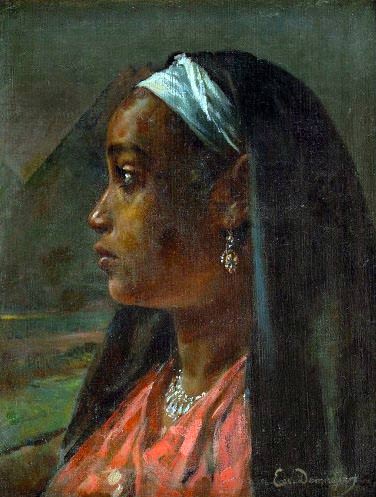

The side portrait of a Nubian girl in her veil, jewelry, and traditional dress, speaks volumes.

This work by Egyptian-Armenian artist Ervand Demerdjian is a respectful, elegant portrait — a marked departure from fetishized colonial representations. The region speaking for itself.

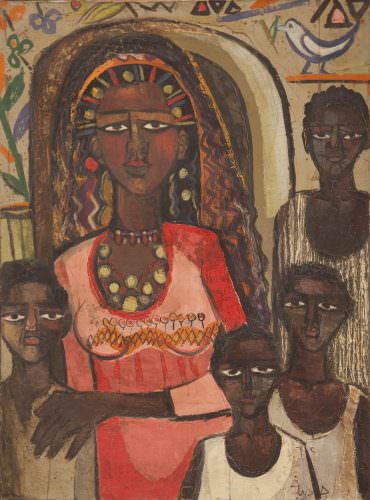

Then there is the Nubian family, painted in 1962 by Gazbia Sirry. She was part of a group of Egyptian artists brought by the government of Gamal Abdel Nasser to depict his mega project, the Aswan dam.

Instead of producing propaganda, Sirry painted the people of the region who would be displaced by the dam and faced an unknown future.

The 1966 painting The High Dam by Effat Naghi shows the dam itself. A chaotic tableau of scaffolding and steel, devoid of people, is meant to communicate the lack of human input in the project.

Paintings by Iraqi communist artists also echo one another, though the artists — as Al Qassemi points out — created their works under starkly different circumstances.

There is Kadhim Hayder who remained in Iraq under Baathist rule and painted in coded symbols.

Hayder’s painting, Ten Fatigued Horses Converse with Nothing (The Martyr’s Epic), shows a group of horses in distress. Some howl at a red sun, while others keel over in despair. The martyr should be an allusion to Imam Hussein, slain in Karbala, and especially revered by Shiites.

But these horses are actually mourning Iraq’s communists — culled when the Baath party seized control of the state. Al Qassemi explains the subtle meaning, gleaned from interviews with friends of the artist, who remained in Iraq.

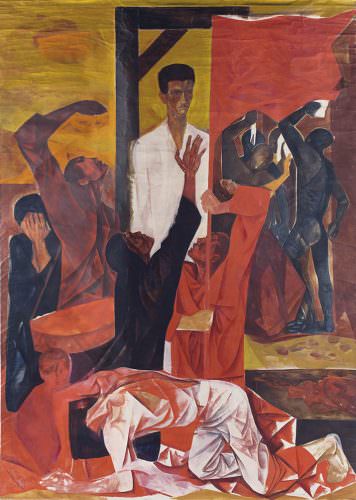

And then there is Mahmoud Sabri, who fled repression in Iraq, thus able to express himself boldly and without fear.

His painting, The Hero, shows an Iraqi communist at the gallows, standing firm, the women around him wailing, a scene that unmistakably mirrors the crucifixion of Christ. It is unequivocally sympathetic to the communists, its creation possible as the artist had fled Iraq.

Al Qassemi is a fountain of knowledge about each artist and painting, constantly pulling up additional details on his phone and going off on tangents on the obscure places works were located, the secret lives of the artists, and the circumstances that inspired them to create.

An abstract painting by Emirati artist Hassan Sharif is notable, Al Qassemi explains, for its medium. Unlike most of the artist’s works, created with trash or done on paper, Black and White is oil on canvas. “It lives for decades… this denotes he wants it to stay.”

He pauses to pay tribute to Madonna of the Oranges by Palestine-born Ismail Shammout, whose family was expelled during the creation of Israel in 1948 and whose 2002 exhibition in Dubai marked Al Qassemi’s introduction to Arab art.

Interform, a flowing wooden sculpture by Saloua Raouda Choucair stands out in the gallery — its polished geometric curves once used, Al Qassemi laments, for umbrellas and coats while it sat on the bar of the Smugglers Inn as the Lebanese civil war raged around it.

“Georges El-Zeenny owned the Smuggler’s Inn bar during the civil war and he kept it on display during the whole war. And then people started putting their umbrellas! She was abused for 15 years during the war!” Al Qassemi exclaims, speaking of the sculpture as if it were part of his family.

Barjeel is in the process of creating in-depth explanatory cards for each work, which visitors can read to go beyond the basic biographical information. As I listen to my collector friend passionately explain, Google and ask about each work, I find myself adopting his sense of urgency, that these stories belong to the public — and especially the Arab world.

“Oh my God, we almost forgot The Last Sound,” Al Qassemi bursts out. “This is the most important work in the collection.”

The Last Sound was painted in 1964 by the Sudanese artist Ibrahim al-Salahi. He was studying in the United States in the 1960s when he learned of his father’s death.

“The work is called Last Sound because it denotes the sound heard when the soul is leaving the body. The last sound is what? It’s the doaa, the prayers. And these prayers are Sufi prayers. That a Sufi Muslim of Sudan would recite.

“The colors are the colors of the sand of Omdurman where his father was born,” Al Qassemi explains, in admiration of every detail. He wants to drive home the message that these modern paintings are thoroughly of this region — not some import from the West.

“Islam, the celestial objects, the moon the stars. The birds denote freedom of the soul. The African mask, Hurufism,” he observes, appreciating the painting’s elements one by one.

“It show his Sudanese, Islamic, African, Arab identity,” Al Qassemi said.

Then, something else catches his eye. It is The Void by Kuwait artist Jafar Islah. The rich, dark tableau is punctured sharply by a thin white rectangle, interrupted on its bottom by two semicircles that jut out.

“That sexual reference down here! Can you imagine? I can’t tell if this is a bum or boobs,” Al Qassemi says kneeling in awe at the painting. “The stereotype of khaleejis is backward,” he said, with a tone of incredulity. “And this was done in the sixties!”

“If I had to save one painting I think it might be this one. I’m married to The Last Sound, but I’m in love with this one … It means we are part of modernism.

We are in conversation with the rest of the world.”

Each work in the collection tells a story, each is interlinked. It is impossible to walk out after a tour with Al Qassemi and not be enthralled.

One degree of separation

Al Qassemi had spent hours in motion, rushing to explain each piece, working to make every moment count, to imprint his message on a new messenger. The drive to his Dubai residence was silent.

Al Qassemi had spent hours in motion, rushing to explain each piece, working to make every moment count, to imprint his message on a new messenger. The drive to his Dubai residence was silent.

That evening was to be one of the last salons, or majlis, Al Qassemi would hold before departing the UAE. To pass through his door felt like an arrival to Dubai.

That evening, like so many before the crowd was warm, interesting, and interested. Pretenses went out the door, as everyone assumed the other must be someone special. After all, Al Qassemi had curated our presence.

There was the architect who’d designed Dubai’s seashell-shaped bus stops, the Soho House interior designer and the king character from Dubai’s signature show La Perle. Not only creatives — a lobbyist for a Gulf monarchy might be sitting next to you. The guests flowed from corners of debate to couches of conversation.

“Couples hold hands,” Al Qassemi remarked of his gatherings. “People don’t do that in public here.”

Each gathering had a slightly different guest list, with regulars, friends, revolving characters, and other people of interest passing through town. There was no “type” at Al Qassemi’s table.

People hailed from all sorts of backgrounds, levels of religiosity or lack thereof, nationality and line of business.

As people filed in, we migrated to the salon. Al Qassemi’s art jumped out at you everywhere, the bold tableaus playing off of the colorful guests.

“You’ve heard of six degrees of separation,” one of Al Qassemi’s business associates said. “Between Sultan and everyone else ‘there is one degree’.”

At that last dinner, many of the familiar pieces of art were absent from the walls. Paul Guiragossian’s La Lampe, once lighting the top of the staircase, now hanging for the public in Sharjah.

The last sound

Since our last supper, Al Qassemi has embarked on his latest chapter, as a Greenberg World Fellow at Yale University, an enrichment program for creatives looking to take a step back from their work, experiment, and possibly shift gears.

“I’m sick of this,” he said, speaking of the business world. “I want to do something else.”

But before leaving the Emirates, Al Qassemi made a decision to return to social media. Initial tweets about art and diplomacy soon gave way to a flood of charged commentary.

Within days and weeks of his social media return, Al Qassemi was calling for museums to institute quotas for minorities, including women and LGBT people, condemning the rise of new skyscrapers with inhumanely small living spaces for maids, and pondering how refugees and those suffering in the region were affected by the concept of capitulation in Islam.

All the while, he was putting his affairs in order, with thoughtfulness and care. He paid tribute to the contributions of immigrants in the UAE, inviting Indian architect Ashok Mody, who designed his family home, to a one-time public viewing of the 1970s structure.

Al Qassemi packed up his office, photo albums and all, his art left behind for the public. The majlis to travel wherever he goes.

This article was originally published in Asia Times on September 23, 2018.