The late 20th century heralded a global effort to introduce multiple modernities to what had been a largely Western-centric understanding and display of modern art. While institutions such as the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City acquired works by the likes of Lebanon’s Saliba Douaihy, Iranian-Armenian Marcos Grigorian, and Sudan’s Ibrahim El Salahi as early as the mid-1960s, none of them would go on display until well into the 21st century.

That they finally did was partly thanks to the work of renowned Nigerian curator Okwui Enwezor, who was behind the groundbreaking 2001 exhibition The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa, 1945-1994. The exhibition finally introduced non-Western modernities on a larger scale into leading Western museums, opening in Museum Villa Stuck in Munich before moving to Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, and finally MoMA PS1 in New York.

The exhibition included works by 50 or so artists, including El Salahi, a native of Sudan who was born in 1930 during the Anglo-Egyptian colonial era. Several decades after El Salahi’s work was first acquired by MoMA, it was finally displayed as part of the exhibition, albeit at an offsite location and for just a few weeks. Back then Salah Hassan, a thirty-something Sudanese scholar and founder and editor of Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, had started to reach out to art institutions about holding a stand-alone show for El Salahi. Little did he know that it would take nearly a dozen years to realize his goal.

“For years I was going from museum to museum, meeting directors and curators and telling them ‘You need to give this man a show, his work is important,’ and none of them would listen,” Hasan told the author in his soft-spoken tone. It was only when he approached Sheikha Hoor al-Qasimi, the president and director of the non-profit Sharjah Art Foundation, that things changed. “She immediately welcomed the idea and offered to hold the retrospective exhibition, which was organized by the then Museum for African Art in New York (now replaced by the Africa Center) and the Sharjah Art Foundation.”

The exhibition Ibrahim El Salahi: A Visionary Modernist opened in Sharjah in May 2012, and travelled to the Katara Cultural Village Foundation in Doha, Qatar in October 2012, and then to the Tate Modern in July 2013, where it attracted over 33,000 visitors. It was a landmark as the first exhibition inaugurated in the Arab world that subsequently traveled to a major Western museum. Hassan also attributes the now historic 2013 Tate Modern show to Chris Dercon, the museum’s then director, and Jessica Morgan, the current director of the DIA Art Foundation in New York, for creating a legacy of inclusion, interest in global modernism, and forward thinking at the Tate.

For decades, Hassan collected, archived, and documented works by Sudanese modernists, including El Salahi. The fact that two historically important and politically significant El Salahi works are now held by the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art at Cornell University, where Hassan teaches, is itself a testimony to his relentless efforts to safeguard the artist’s legacy.

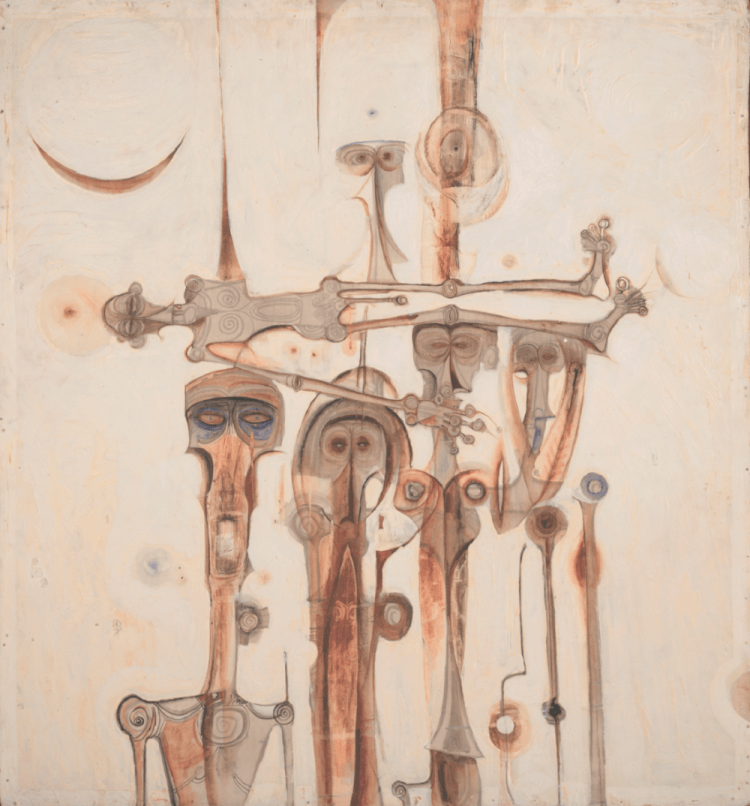

The two works — Funeral and the Crescent from 1963, one of El Salahi’s greatest masterpieces, and The Inevitable (1984-85) — took more than a decade to locate. “There were missing works,” Hassan explained. “There were no records for either piece.” But his dedication paid off, and for Hassan it would be unfathomable to hold a major retrospective of El Salahi without these two works.

El Salahi painted Funeral and the Crescent in honor of Patrice Lumumba (1925-1961), the Congolese independence leader. The first elected prime minister of the Democratic Republic of Congo, Lumumba served for only 80 days before he was executed by Belgian-backed forces, and his assassination became a rallying point for decolonization and the struggle for independence in Africa. In his effort to locate this statement artwork, Hassan had little to go on. Few records were kept about it, other than that when it was published in the African Arts journal in 1969, alongside an article on El Salahi’s work, its ownership was attributed to a Mr. and Mrs. Marker. Hassan began the long and arduous process of locating the owners and the treasured painting by first asking El Salahi himself. When they both drew a blank, Hassan continued his search, and eventually he found a physician in Washington, DC named Ralph Marker that had a keen interest in African art. The Markers had most likely bought Funeral and the Crescent from Elizabeth Hurley, the wife of Granville W. Hurley, Sr., an engineer who worked at the Khartoum USAID office in the early 1960s. Mrs. Hurley, who was living in Washington, DC, but was based in Khartoum at the time, had borrowed a large number of works by El Salahi with a promise of selling them for him in the United States. However, other than the fact that Mr. and Mrs. Hurley had retired to the Washington, DC area, Hassan had no further leads.

The real breakthrough came when Janet Stanley, the head librarian at the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art, told Hassan that Mrs. Marker used to attend events at the museum and was still living in a suburb of Washington, DC. Searching online, Hassan found an address and phone number for the Marker family in Virginia. To his surprise, when he rang the number a woman answered the phone. When he asked to speak to Mr. Marker, the woman, Marissa Marker, responded, “You’re speaking to his widow. I’m afraid my husband passed away many years ago.” Hassan expressed his condolences and introduced himself briefly. “I would like to ask you, if I may, about a particular painting. It is a work by a Sudanese artist known as Funeral and the Crescent and was published in the African Arts journal in 1969.” Mrs. Marker replied that she knew the painting well. “In fact, I am looking at it right now above the mantle of my fireplace.” Hassan breathed a sigh of relief; the painting had finally been found. His next question was the boldest yet: “Would you consider gifting it to a museum in the name of both yourself and your husband?” After a brief exchange Hassan’s job was done: he connected her to Franklin Robinson, the director of Cornell University’s Herbert F. Johnson Museum, which is now home to Funeral and the Crescent.

The Herbert F. Johnson Museum also holds what is arguably El Salahi’s most important large ink painting, The Inevitable (1984-85), which depicts Sudanese protesters rising up against the military government of Jaafar al-Nimeiri in 1985. Hassan played a key role in its acquisition as well by bringing it to the attention of the museum, which in turn worked to establish a fund for its purchase financed by gifts from donors.

Sheikh Ibrahim El Salahi, as he is often addressed to signify respect and societal standing, is an iconic artist whose work redefines modernism away from the Eurocentric misunderstanding of the past century. His work is a pillar of global modernism, and some — this author included — would go so far as to say that 20th century art cannot be understood without giving his body of work its rightful place in history, whether that be in museums or academia.

This article was originally published in Middle East Institute on March 12, 2019. A screenshot of this article can be downloaded here.