Giving a voice to the people.

Egyptian artists have a long history of political engagement. Even in the mid-twentieth century, when they mostly relied on state funding, they made critiques of the ruling regimes, and created one of the few spaces where independent political thought could brew. Egyptian artists—like their counterparts in many other countries in the region—have long been in closer touch with the mood of average people than the repressive governments have been, and they have served as both bellwethers and instigators of change. When the revolution broke out in 2011, Egyptian artists were thus well positioned to take on a much more direct, activist role, and many did. Art changed as well, becoming more accessible and purpose-driven. Now, as the tide again has turned to authoritarianism, the unbridled hope of the uprising has waned, negatively affecting art as much as any other part of the revolution. Yet there are glimmers of dissent in the art that lives on, and many reasons to think that Egyptian artists will be part of the vanguard of the next wave of social and political change, whatever it may be.

Just after 3:00 a.m. on the morning of Friday, June 15, 2012, four young Egyptians, armed with spray cans and stencils, crept through the Cairo night. It was ten days before Egypt’s historic post-revolution election, the first free one in history. Their leader, underground artist El Zeft (a word that translates into “asphalt” but in colloquial Arabic is used to denote rubbish), took them to the former headquarters of the National Democratic Party (NDP), not too far from Tahrir Square, the site of the Egyptian uprising of 2011. The NDP was the political party associated with the corrupt three-decade rule of Hosni Mubarak, and the building was slated for demolition after the party was disbanded by court order and had its assets seized. The four men, all in their early twenties, were careful not to alert the officers guarding the building.

The activists silently approached the wall next to the main gate and quickly spray-painted two words, “Opening Soon,” using a stencil designed by El Zeft. Photojournalist Jonathan Rashad had, within seconds of its completion, snapped a picture of the graffiti that went viral on social media even before the Friday noon prayers later that day. The message: Egypt may be about to vote, but too many signs pointed to a reemergence of the repression and authoritarianism of the ancien régime. The army immediately dispatched a team to paint over the graffiti, but it was too late. It was the talk of the town that week in Cairo.

It was also prescient. The freely elected if inept and divisive government of Mohamed Morsi would last little more than a year before being unseated by a coup, which in turn would lead to the installation of the current president, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi. And Sisi’s regime would soon prove to be even more suffocating than the NDP’s.

El Zeft’s graffiti bombing was, in a way, the zenith of a period of activist popular art in Egypt, when artists and revolutionaries worked hand in hand, and were often one and the same. For decades, Egyptian fine arts had been supported and managed by state patronage. During that time, Egyptian artists accomplished much, including making works of beauty that often contained subtle critiques of the social and political status quo. The artists created a community with their salons and expositions that became one of the few fonts of independent political expression of any kind. For many years, state repression circumscribed the community’s broader impact. But when the uprising of 2011 began, Egyptian artists were well positioned to play an important role in responding to the unrest and creating iconic imagery. Their passion for social justice and political change was evident in their work and activism.

The occupation of Tahrir Square, and the revolution that followed, broke open bold new spaces for Egyptian artists. They in turn broke open new spaces for political discourse. Some of the older generations of artists never got much involved with the revolution, but others happily forsook the comfort of galleries and the competition for state support in favor of the street. For a time, the lines between high- and lowbrow were blurred, and Egyptian art experienced a dynamism and immediacy unseen in recent history, as it engaged directly in political tumult. Creators like El Zeft, who had little or no professional training, were all of a sudden propelled into the limelight as major voices calling out for change on the streets of Egypt.

The pattern of melting boundaries and the flourishing of art as activism repeated itself throughout much of the Arab world during the years of the uprisings. But in Egypt as elsewhere, it didn’t last. As the uprisings faltered, cynicism spread in the art world, as it did in other sectors of society. Activist street art, quick to flare in importance during the first two years of the revolution, very quickly receded to its margins under the repressive control of Sisi’s rule. The pool of active artists has shrunk. Yet many have continued to create, express, and comment, and remain a highly relevant cultural force—one of the few alternatives to the stultifying mainstream political dialogue.

To trace the history of Arab art from the mid-twentieth century through the uprisings and to the present reveals a great churning of ideas, social awareness, and activism that are not evident in the study of official politics. Arab art has tapped into alternative, popular histories, within boundaries that contract in times of authoritarianism and expanded during the uprisings to unprecedented levels. The creative fire of these artists has never been extinguished. Egypt’s fine arts community—even during the regimes of Gamal Abdel Nasser, Anwar Sadat, and Mubarak—grappled in meaningful ways with fundamental political questions, though artists’ direct involvement with political struggles was minimal until the uprisings. The surge of politicized artists who occupied Tahrir from 2011 to 2013 was exceptional in Egypt’s history, but also echoed the political activism and engagement of earlier generations of Egyptian artists.

In this report, I attempt to follow that story in broad strokes, focusing on the visual arts in Egypt but with an eye toward other countries in the region as well. I am especially interested in the interaction of art and politics—cases like El Zeft’s where the raw need to express dovetails with a movement for political change. However, I do not view art solely as an accessory to politics. Political scientists might try to gauge whether art is a valve, releasing pressure created by authoritarianism, or a force that foments change. But for me this question is only a small dimension of art’s importance. Art in the Arab world has been, and continues to be, almost divinatory. As such, I follow the history of contemporary art to highlight the moods and ingenuity of the artists and their societies, and also to get a sense of where they come from and where they may be heading next.

In that vein, Egyptian art points us to a future of continued political engagement and an intense desire for social progress that the new authoritarians are quite unlikely to deliver on their own. Artists are mobile, vocal, and ever more clever with pushing boundaries. The fervor and optimism of the revolutionary days of only a few years ago may have subsided and organized political blocs may have fractured. But the new strongmen of Egypt are unlikely to succeed at completely boxing in expression.

Egyptian Art in the Postcolonial Era

The twentieth century was tumultuous for Egypt, but a period in which the country’s creators of fine art—al-fanoun al-jamila—found their footing and even flourished. Ironically, successive Egyptian regimes’ repression managed to give a boost to fine art, even as they caused other forms of expression to wilt. Nasser (president from 1956 to 1970) and his successors had a respect for fine art, and considered its achievements a point of national pride. At the same time, they believed it to be mostly appreciated by elites, and therefore not dangerous. Thus, they gave artists grants and wide latitude to create what they liked, even if it subtly critiqued the state or the status quo. As long as what they created wasn’t consumed or obvious enough to be appreciated by the masses, fine artists were mostly allowed to paint and sculpt as they pleased. As a result, a great deal of creative energy was channeled into the fine arts.

Yet despite their state patronage, Egyptian artists were engaged from the beginning in politics. Their postcolonial political engagement has roots in the struggle against the British and the monarchy they supported. Some later evolved into propagandists, but many did not, and kept their independence.

The Monarchy under British Occupation, 1922–52

As early as the mid-1930s, a group of Egyptian intellectuals and artists influenced by surrealism and headed by author Georges Henein (1914–73) came together and launched the Art and Liberty Group. The movement was socially liberal, and favored anti-capitalist economics and Freudian psychological ideas. But it also extended deeper into attacking the British occupation of Egypt, Egyptian monarchists, exploitation of women and workers, and Islamic nationalism. The movement lasted for just a decade, from 1938–48, eventually disbanded by the Egyptian police and British Occupation Forces at the beginning of the Cold War. However, its impact was long-lasting and it has enjoyed a revival in 2016–17 with a series of exhibitions at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris and the Sharjah Art Foundation in the United Arab Emirates (U.A.E.).

During this period, one of the most noted incidents of artist political activism within a work of art was that of Abdul Hadi al-Gazzar (1925–66), the son of an Alexandrian religious scholar. In 1951 when Gazzar was twenty-six years old, he submitted a painting to an exhibition at the invitation of his teacher, Contemporary Art Group founder Hussein Youssef Amin (1904–84). The work, which goes by several names but is most commonly known as Hunger, is now one of the most famous paintings in Egypt. It depicts a group of eight barefooted women and a child, standing side by side with empty plates in front of them, signifying poverty. Hunger was regarded as a clear criticism of the monarchy and the ruling elite, and resulted in Gazzar being briefly detained along with Amin. Both men were released following an intervention by the renowned Egyptian lawyer-artists Mohammed Nagi and Mahmoud Said. Following his release, Gazzar painted a second version of Hunger, after the original was sequestered, according to an interview conducted by researcher Fatenn Mostafa Kanafani with the late artist’s wife Laila Effat.

There was also artistic activism directed externally. Henein, of the Art and Liberty Group, coordinated with French surrealists to defend artistic freedom and speak out against Hitler’s destruction of “degenerate” art. The Group, which included artists such as Ramsès Younan, Fouad Kamel, and Kamel El Telmisany, announced their “Long Live Degenerate Art” manifesto in 1938. (Henein would later break with French surrealist friends over their support for the state of Israel, whose creation and treatment of Palestinians would be a major focus of Egyptian artists for years to come.)

The period of the monarchy was thus marked by significant antagonism between artists and the Egyptian state. In subsequent decades, the government’s relationship with artists was not always adversarial. In fact, the artists under Egyptian government patronage produced much work that advanced government policies and ideas. But whatever the nature of their advocacy and relation to the state, by the middle of the century it was well established that Egyptian artists were, by nature, political.

From Nasser to Sadat: 1952–81

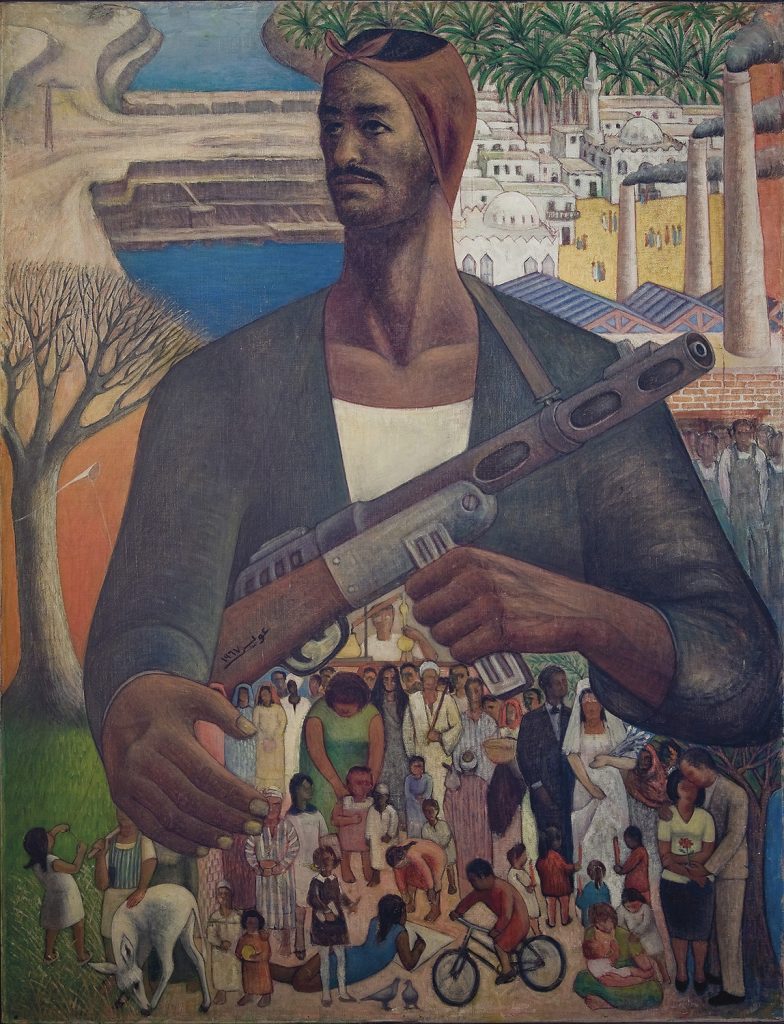

After the revolution of 1952, Egypt, like Ba’athist Syria and Iraq, reserved a part of its budget for culture and viewed state-sponsored art as a significant arm of government information or propaganda policy. State-supported and independent artists didn’t necessarily disagree at all times. Common causes such as the rejection of colonial rule and, later, anti-Zionism brought together governments and artists from opposite ends of the political spectrum across the Arab world. For instance, painter Hamed Ewais (1919–2011) repeatedly created works commissioned by Nasser’s government during the nationalization of the Suez Canal9 and even after Egypt’s defeat in the war of 1967.

The early years of Nasser’s rule were a time of great pride in many national endeavors, and for some, significant hope about the future. In their enthusiasm, some artists who had staunchly opposed the monarchy became near-propagandists for the government. For example, Gazzar, the painter of Popular Chorus, embraced the new republican regime. One of his most famous paintings, The Charter (1961), depicts a woman wearing a crown, holding Nasser’s manifesto. The piece, which is now exhibited in the Egyptian Modern Art Museum, instantly became an icon of the 1952 revolution.

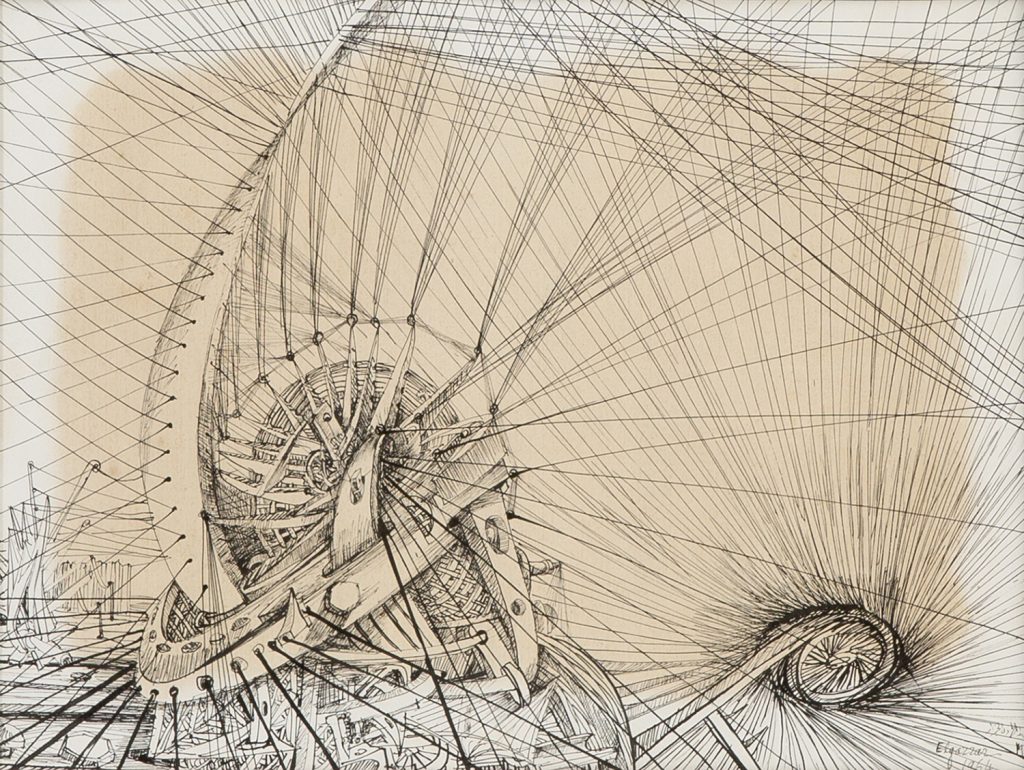

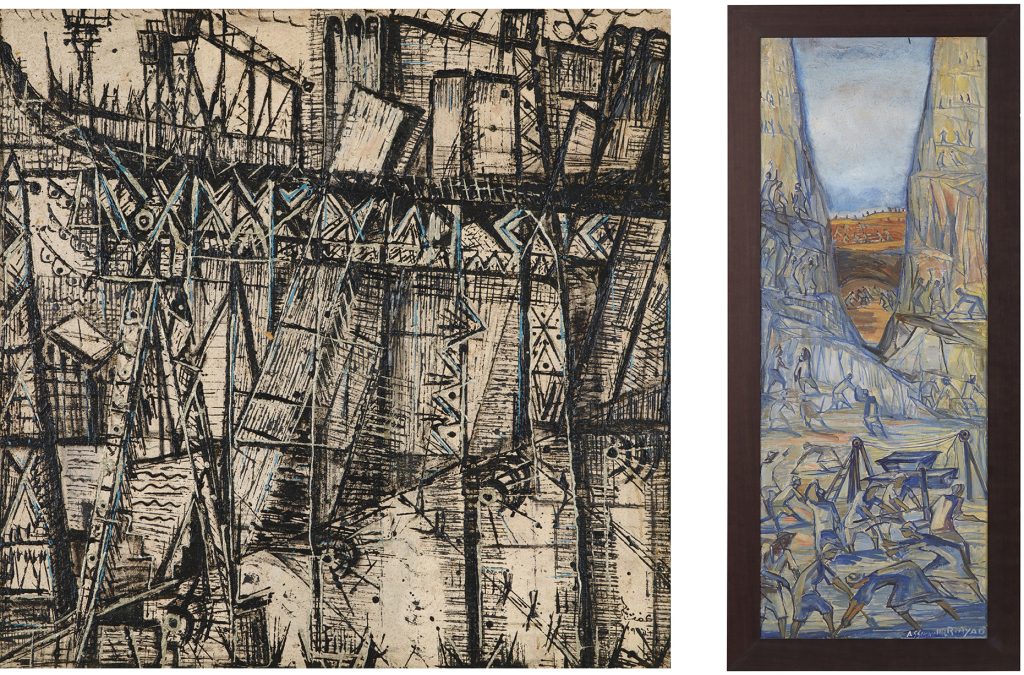

Alternatively, artists who received government grants to travel to the Aswan High Dam construction site, like the painters Tahia Halim (1919–2003), Ragheb Ayad (1892–1982), and Effat Naghi (1905–94), offered critical insights into the precarious nature of the massive project. Halim, who documented Nubian villages in her paintings before the construction of the dam flooded them, showed how potentially destructive the government project could be by offering a glimpse into the lives of villagers who were forced to permanently resettle. Ayad and Naghi were similarly commissioned by the state to document the building of the dam in the 1960s. In both artists’ work, we see different approaches that depict a less glorified image of the project than what the government usually promoted. In Ayad’s 1964 painting Aswan, his waif-like characters seem to be laboring endlessly upon various heights of rocky terrain. His composition is arranged in such a way that each worker loses his individuality and appears like one of many hieroglyphic slaves constructing the Pyramids of Giza. Naghi’s documentation focuses on the scaffolding that appears like a teetering edifice of wood and metal, and eliminates the presence of laborers altogether. Naghi’s approach takes the loss of humanity in Ayad’s work further and highlights the precarious nature of the ambitious dam project.

Implicitly critical as they were of projects like the High Dam that were usually cornerstones of patriotic propaganda, these artists’ work had limited popular and certainly minimal political impact. The works appeared in museums, and though beautiful and affecting, did not reach the masses. Nor did they spur any elite revolt against the country’s leadership. It would be decades until satellites and the Internet could convey images to broader audiences, but in any case the style of mid-century art was removed from the tastes of the vast majority of Egyptians, and its critiques were delivered with too much subtlety to have had a direct impact on politics. Nevertheless, the artists managed to continue their community’s tradition of dissent.

But artistic freedom stopped at the edge of the canvas, as Inji Efflatoun (1924–89) found out. Born to a well-to-do French speaking family, Efflatoun studied under Telmisany, who introduced her to his Art and Liberty Group during her studies at Cairo University in the early 1940s. Efflatoun also joined the Egyptian Communist organization Iskra and a number of feminist organizations. Operating under Nasser’s regime, Efflatoun’s staunch Marxist political leanings and active participation in demonstrations were punished when the government issued a decree that authorized the detention of women taking part in political activism. Along with twenty-five other female political activists, Efflatoun was incarcerated from 1959 to 1963. During her time in prison, Efflatoun continued championing the cause of the working class, painting peasants, laborers and her celebrated series of women prisoners.

Anwar Sadat (president from 1970 to 1981), like his predecessor Nasser, tried to silence his critics, including intellectuals and artists. He became even more notorious than Nasser, however, for his blanket blacklisting of artists such as painter and sculptor George Bahgoury (1932– ) who was exiled from Egypt and spent many years in Paris. Following the signing of the Camp David accords, Bahgoury published Banned Artworks, his famous book of caricatures mocking Sadat.

Sadat did, however, support art when it aligned with his agenda. In a move that Sadat may have organized, and certainly tolerated, the works of Egyptian modern master Mahmoud Said (1897–1964) were exhibited under the patronage of the newly inaugurated Egyptian Embassy in Israel at the Habimah National Theatre in Tel Aviv, in February 1982. The following May, Israeli artists were invited to showcase their work at Cairo’s Le Méridien hotel. However, no other exhibitions took place in the following years, probably partly due to significant objections from Egypt’s intellectual elite and artist community, which almost unanimously rejected—and continues to reject—normalization with Israel. For instance, Ali Salem (1936–2015), a famous Egyptian playwright, was expelled from Egypt’s Writers Syndicate following his numerous visits to Israel, which began in 1994, and his open calls for normalization.

Throughout this time, artists continued their expression about international political and social issues. They commemorated the Nakba (or “Catastrophe,” as the events surrounding the 1948 founding of the state of Israel on historic Palestine are known in the Arab world), and the defeat of the Arab armies in 1967, known as the Naksa. They mourned the massacre of Sabra and Shatila in Lebanon in 1982, and celebrated the independence of their countries from colonial powers. All of these events were of earnest importance to broad swaths of the region’s societies.

Regional Patterns of Repression and Expression

There was a similar pattern in other parts of the Arab world. In the Ba’athist states of Iraq and Syria, the governments embarked on programs to train and fund artists in the hopes of instilling a sense of national identity through art. Similarly, Algeria and Morocco were trying to shake off the decades of French cultural influence by supporting or tolerating artists such as M’hamed Issiakhem (Algerian, 1928–85), and Farid Belkahia (Moroccan, 1934–2014) and Mohammed Melehi (Moroccan, 1936– ) of the Casablanca Group. Kuwait, Tunisia, and Sudan also witnessed a burgeoning art scene with the founding of galleries and art societies in the 1950s and 1960s.

In fact, from the mid-twentieth century onward and across the Arab world, art societies formed in cities such as Baghdad, Kuwait City, Khartoum, Tunis, Casablanca, and elsewhere. These societies were registered by the state and sometimes received subsidies and support, and as such they were not directed against the state. However, they contributed to the production of original works with political relevance.

For instance, in the 1970s Algerian authorities commissioned the French-trained Issiakhem (who, as researcher Amina Menia notes, was an anti-colonial freedom fighter before becoming a recognized sculptor) to create a sculpture to replace the famous Monument to the Dead, which Paul Landowski made in 1928 to commemorate the fallen French and Arab soldiers of World War I. By the 1970s, the French-commissioned monument was considered an offensive relic of colonialism. Issiakhem used a large sarcophagus to enclose the sculpture as a sort of tomb, perhaps as a metaphor for the death of colonialism in Algeria.

In Iraq, master artist Jewad Selim (1919–61) erected a massive government-commissioned frieze in central Baghdad titled Monument of Liberty in 1961. The Iraqi government commissioned the giant work to commemorate the July 14 Revolution of 1958 that led to the overthrow of the British-backed Hashemite monarchy. The bronze work comprised twenty-five human figures spread across more than two-dozen panels along with depictions of a horse and a bull, in what could be considered a nod to Picasso’s Guernica.

Both the Algerian and Iraqi works were far from being critiques of the governments that commissioned them, yet they were hardly propaganda. Instead, they reflected popular sentiment and contributed to a vibrant mid-twentieth century arts scene that still resonates today, long after the regimes that paid for them have disappeared. As in Egypt, despite state patronage, artists’ communities became petri dishes for other kinds of political change, over which the governments that sponsored them had little ultimate control.

Mubarak and the Dissolution of State Control: 1981–2011

Although Nasser and Sadat both pandered to intellectuals, Mubarak took things a step further by appointing abstract painter Farouk Hosny as his minister of culture, where he remained for twenty-four years. This maximized Mubarak’s ability to control the arts, by directing funding and overseeing state-run exhibition spaces. The co-option was far from complete, however. As calculating as Mubarak’s art patronage was, there were bigger forces at play that undermined his efforts—namely, the global information revolution, and the rise of a private regional art market that was closely linked to it, loosened the binds of state patronage.

In the twentieth century heyday of state-sponsored art in the Arab world, there was no art market to speak of and few, if any, galleries. Most artists were teachers who sold works on the side, and were not dependent on buyers. By the turn of the twenty-first century, this had begun to change. By the second decade of the new century, it was all but upended: satellite television, streaming video, and social media sites enabled young artists who had emerged since the late 1980s to see events that touched others’ lives in immediate terms. Contemporary artists became more dynamic and able to react more spontaneously, and with wider reach. Also, far greater access to private funding became available to the young artist, thanks to a proliferation of galleries across the region. Direct criticism of government might be hazardous to an artist’s physical safety, but it was no longer a direct threat to his pocket book.

Collectors in the wealthy Arab states of the Gulf were a major force in the creation of this private market. Dubai emerged as the Middle East’s most important market for art. Scores of galleries opened in its industrial and financial centers, and Christie’s and local galleries such as Ayyam conducted auctions.

In some cases, these museums and galleries specifically sought out politically relevant works from Arab artists. Part of the impetus for such collections was historical; after a tumultuous few decades, institutions saw collecting art that documented and commented on these events as being part of their public duty. Also, with a diversified economy and large expatriate populations taking advantage of the region’s wealth and growing engagement in global commerce, public opinion began to demand an arena in which to view such artworks. In the Gulf, several museums were established, including Doha’s Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art (established 2010), Abu Dhabi’s Guggenheim (established 2006), and several others. A painting that might have been censored in Egypt—or which an Egyptian artist might have been reluctant to even create at home—found a warm reception in Abu Dhabi, Doha, or Dubai.

By the first few years of the twenty-first century, independent cultural venues had also started appearing in cities in other parts of the Arab world, and especially in Cairo. Sakia El Sawy (Sawy Culture Wheel), which opened in 2003, became one of the most popular. The Sakia, as it is commonly known, was perhaps the first non-government-affiliated cultural center in the country. It was founded by Mohamed Abdel-Moneim El Sawy, whose father is an acclaimed novelist and a former minister of culture. Within a short period of time the Sakia was hosting daily events, including concerts, puppet shows and art performances, drawing 20,000 monthly visitors by 2009.

Another milestone was the establishment in 1998 of the Townhouse Gallery by a Canadian expatriate in Cairo named William Wells. The gallery hosted groundbreaking and socially engaging exhibitions. Writing for the Middle East Institute in 2015, Maria Golia noted that the gallery “opened its doors at a time when the state exercised mind-numbing control over cultural venues and artistic output so that its establishment was tantamount to a political act.” Having been labeled a Zionist enterprise in the Arabic press, the gallery was repeatedly raided in its early years; in time, though, the proliferation of art galleries meant that it was no longer the sole target of negative attention.

The Rise of the New Media

In Egypt in particular, there was another factor that, perhaps coincidentally, undermined Mubarak’s strategies for managing expression even more. Through the 1980s and 1990s, modern art gave way to contemporary practices, and a new generation of artists emerged whose media were harder to control through government funding and state promotion. Photography and video became more widely used, conceptual approaches made their debut, digital devices and media became available, and the dwindling cost of transport meant that complex works could be created or assembled abroad, and could be shipped internationally to be loaned for exhibitions. These developments gradually loosened the government’s control over the arts industry. Cutting-edge, vibrant forms of expression were now being created outside the patronage of the state.

Among this new generation of contemporary artists is the sculptor Moataz Nasr (1961– ) who has, since the early years of the twenty-first century, created socially conscious works, including An Ear of Mud, Another of Dough. Made of clay and dough ears, it symbolizes the deafness of the ruling class’s ears to the plight of most Egyptians. Nasr also established the group Darb 1718 in 2008, dedicated to promoting social change through art.

The degree of freedom that artists had obtained around the turn of the century may not have seemed like a threat to Mubarak at the time. But the astute connoisseur could have read something of the future in the works that were emerging from Egypt toward the end of the first decade of the twenty-first century.

Indeed, many of the region’s artists had an uncanny ability to capture the mood of their country and even foresee its problems. Cairo-born painter Walid Ebeid’s (1970– ) 2005 work Outside Prisoners depicts men, women and children, money in hand, clamoring to buy bread, where there clearly isn’t enough for all of them. The perspective is from within a stall with prison-like bars, stopping them from making the payment. Little do those in the back know that there are just six or seven loaves of bread left. Another of Ebeid’s works, the 2007 painting Under Investigation, depicts a young man, possibly in his twenties, sitting on a stool with his back to the viewer. The man’s white t-shirt is lifted, unveiling bruises and others signs of torture and beating. In Ebeid’s work we see a much more contemporary strain of Arab art that directly antagonizes the state: claims of torture, especially in the last years of Mubarak’s reign, contributed to the outburst of anger that occurred in January 2011. Huda Lutfi, Professor Emerita of Arab Cultural History at the American University in Cairo, created a work in 2008 titled Democracy Is Coming. The work features the familiar face of Egyptian diva Umm Kulthum with a halo over her head and an inscription that reads “democracy is coming,” as military planes fly above.

The quickening pace of change of communications technology during this period further undermined Mubarak’s methods at control. Social media gave artists vastly greater and more immediate visibility, and it also allowed them to market their works directly, rather than going through a gallery. In some instances galleries might shun politically sensitive works, but artists could sell such pieces directly to collectors from their studios. This was the case for the Barjeel Art Foundation, which I founded in 2010 in the United Arab Emirates, when it acquired Jeffar Khaldi’s Good Stamp (2009), which depicts Gulf Arab officials seated in a meeting hall with images of women that look like Lebanese crooner and sex symbol Haifa Wehbe, or American actress Pamela Anderson, loitering in their minds and bodies. Further, in addition to the established Cairo galleries, a number of underground pop-up shows started appearing in the city. These pop-up shows were hosted in artists’ apartments and other common spaces, where they could be free of any state-imposed restrictions.

The later Mubarak years witnessed a further marginalization of the creative community in Egypt, affecting writers, journalists, and artists. But marginalization, in this new era of private art markets and amplifying technology, was far from neutralization. Sometimes, it was the opposite. The Mubarak regime might have heeded the hints of popular discontent about food prices, for example, and made incremental reforms that could have headed off a wider crisis of government legitimacy. Instead, Mubarak and his ministry of culture ignored signals from the fine art sphere, and overshadowed the work of socially conscious artists like Ebeid with inoffensive abstract works, ever widening the gulf between the government and the people.

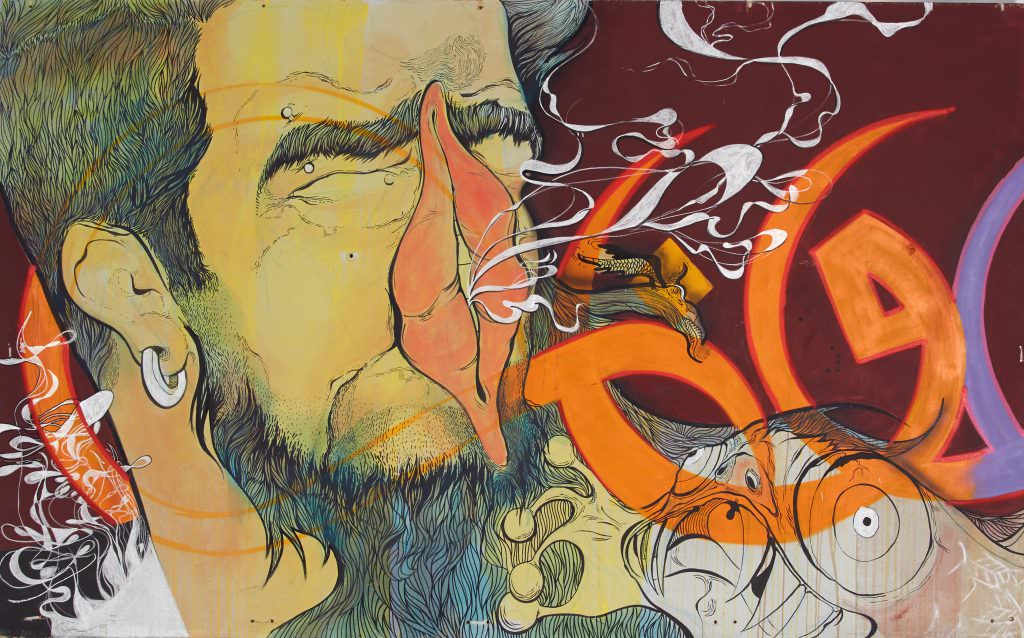

In the years leading to the 2011 uprising, there was a final, significant change in the Egyptian art world: graffiti art became legitimized. It was a development spurred in large part by artists under 30, who did not always conform to more traditional expectations of what art should be. For them, Cairo itself became a canvas, and new media meant that their imagination was no longer limited by the physical constraints of older forms. It was this development that more than anything else heralded a new era for Egyptian artists, who were beginning to engage directly with the broad swaths of the public through art that was overtly political.

The Uprisings

It’s impossible to know exactly to what degree art contributed to the actual outbreak of the Egyptian revolution, but it certainly anticipated the anger that propelled it. And when the uprisings of 2011 erupted, artists were primed as never before to take part in the turmoil.

Take the case of Nasr, the Egyptian multimedia artist. Where his creations had tackled social and political issues in oblique and symbolic (though still provocative) ways in the middle of the first decade of the twenty-first century, they now became explicit commentaries on the revolution. In 2012, he created El Shaab (The People)—twenty-five ceramic figures representing characters from the 2011 uprising. It is part of this sculpture, depicting a dark event that happened on the streets, which sets the work apart. On a separate shelf, but part of the same work, Nasr placed figures representing three police officers tugging at a young woman and dragging her along the street so that her bra was exposed. This was the famous “Girl in the Blue Bra,” whose violent beating at the hands and feet of the police, in Cairo in December 2011, was captured by Al-Masry Al-Youm photographer Ahmed al-Masry. In 2012, thousands of Egyptians still treated this horrific scene as a rallying point for their continued protests calling for revolutionary demands to be met, and for the Supreme Council of Armed Forces—the military body that was then running Egypt—to hand over power to a civilian head of state through democratic elections.

The same image of the “Girl in the Blue Bra” was used by Egyptian artist Nermine Hammam (1967– ) in a photo series that juxtaposes iconic images from the revolution with serene images drawn from Japanese landscape painting. Morocco’s Zakaria Ramhani (1983– ) also references this scene in his piece You Were My Only Love (2012); Palestine’s Shadi Alzaqzouq featured women’s underwear and protest, perhaps inspired by the same moment, in his painting After Washing (2012).

In 2012, at the height of the presidential election season, Egypt-born Australian artist Raafat Ishak (1967– ) created Nomination for the Presidency of the New Egypt. The artwork is a fictional manifesto by a presidential candidate created on a series of fiberboard panels that unfold like a scroll. Some Egyptians laid the blame for the deterioration of the economy on decisions taken under the country’s socialist president, Nasser. In that regard, the manifesto by the candidate comes with a radical promise to dismantle the Aswan High Dam in order to reintroduce the annual flooding of the Nile, alluding “to a metaphoric deconstruction of Egypt’s turbulent history and a political rebirth of the country.”

Some artists, especially graffiti artists, also had an even more direct role in the Egyptian revolution. Savvy with digital media and deeply invested in revolutionary goals, they were able to articulate the people’s demands, or the chance to realize them, into a symbol. Ganzeer’s Mask of Freedom (2011)—depicting a figure with a ball gag and blindfold—was a potent message about the lack of freedom of expression, which was prominently circulated in the beginning of that year. In a Cairo protest in which I participated in 2012, activists handed out spray cans and a stencil created by El Zeft. Hundreds of people used them to paint phrases like “We won’t forget you” and “Glory to the martyrs.”

And in the first three years following the 2011 uprising, Mohamed Mahmoud Street, which is adjacent to the old campus of the American University in Cairo, served as a shrine to the fallen icons of the uprising. It featured images of Khalid Said, whose death in 2010 was one of the sparks for revolt. A mural of Coptic icon Mina Danial reaching out to Muslim cleric Sheikh Emad Effat (both shot and killed in 2011 protests) was interlaced with politically charged phrases. Writing in 2012, critic and blogger Soraya Morayef noted that “the Mohamed Mahmoud wall remains the most powerful tribute to the revolution.” These works resonated with passersby who would stop and take photos, recognizing some figures, and the street came close to becoming a tourist attraction in its own right. It was a site for protests, as well. In November 2011, it erupted in clashes as security forces attempted to violently disperse a crowd of two hundred protesting family members of those who had been killed in earlier demonstrations. Similarly, following the death of seventy-two football fans in Port Said in February 2012, Mohamed Mahmoud once again became a rallying point with paintings depicting the fallen fans. Perhaps eager to turn a page, at three o’clock on a September 2012 morning, the Egyptian government dispatched workers to paint over the graffiti on Mohamed Mahmoud street.

Regional Reverberations

The Arab uprisings featured in works of artists outside Egypt and across the region and in the diaspora. Beirut-born Ali Cherri (1976– ) lived through Lebanon’s devastating civil war and is considered to be a promising artist of his generation. His 2014–16 aerial maps print series Paysages Tremblants (Trembling Landscapes) is an attempt to capture the underlying tensions in Middle Eastern and North African cities, including Beirut, Damascus, and Algiers (an entire set has been acquired by the Guggenheim Museum in New York). Perhaps Cherri’s work that most obviously references the Arab uprisings is I Carry My Flame (2011). It was created mere months after Tunisian street vendor Mohamed Bouazizi set himself alight, thereby kick-starting a series of convulsions that have since rocked the Arab world. In that artwork, eight stills are taken from a YouTube video of an unknown individual (not Bouazizi) who embarked on an act of self-immolation. Even the process of creating these works using serigraphy or silkscreen printing, where ink is forced through a fine screen onto the paper beneath, reflects the violence and duress that an individual set on fire experiences. Finally, Le Grand Vide/Statue Assad features a 2011 photograph of the remains of a sculpture of Syria’s Hafez al-Assad that was pulled down in the early days of the Syrian uprising. The name of the work is also remarkable, denoting the void that was created following the collapse of the regime in some parts of Syria, a void that extremist groups were all too willing to fill.

The politically minded artists of the mid-twentieth century produced fine, powerful works of social commentary, but they had never so directly attacked a ruling regime. Even works that antagonized the government had nothing like the immediacy and relevance of those that commented on and contributed to the Arab uprisings. The artists of the uprisings also engaged a completely different demographic, those who would generally not be included in the political discourse of the past.

The brief free political space created following the Egyptian uprising also allowed for more politically engaging works to be shown in public. After years of making underground art, many artists came to the forefront following the revolution. Art exhibitions were more daring and thought-provoking, and attracted a more diverse crowd. In fact, art openings became places for nonartist activists to meet each other and discuss the latest political developments. The space was so vibrant that some artists in Cairo used their apartments to host semi-underground pop-up exhibitions that lasted for the evening.

In the wake of the uprisings, the Sakia also became a venue for political engagement, such as when it hosted Alaa al-Aswany, the novelist, in February 2012, drawing hundreds of men and women. Aswany began that talk with a moment of silence for Egypt’s martyrs and railed against the “unconstitutional and illegal” rule of the military council.

But the fact that such art existed and played a role in the uprisings should not be confused with the idea that the artists now enjoyed more safety, any more than any of the other revolutionaries did.

A famously tragic example is that of Ahmed Basiony (1978–2011), a thirty-three-year-old Egyptian avant-garde visual artist who was shot dead by sniper fire on January 28, 2011, three days after the start of the Tahrir Square protests.

Basiony’s artistic career—which was not, for the most part, expressly political—was cut short by the revolution, which he deeply believed in. On January 26, two days prior to his death, he posted what became his last public statement on his Facebook page. “Please, O Father, O Mother, O Youth, O Student, O Citizen, O Senior, and O more,” Basiony wrote, “You know this is our last chance for our dignity, the last chance to change the regime that has lasted the past thirty years. Go down to the streets, and revolt, bring your food, your clothes, your water, masks and tissues, and a vinegar bottle, and believe me, there is but one very small step left. . . . If they want war, we want peace, and I will practice proper restraint until the end, to regain my nation’s dignity.”

Following his killing, Basiony “quickly became a potent symbol to protestors of the sacrifices they had to endure in the course of their struggle.” Al-Masry Al-Youm, a popular newspaper, included Basiony’s photo on the front page of its now historic post-uprising edition under the headline, “The Flowers that Bloomed in Egypt’s Garden.”

Basiony was shot for protesting, not for his art. Posthumously, however, it becomes more difficult to draw a line between the two. He was an artist who fully committed himself to his beliefs. Those who appreciated his art evidently recognized this: four months after his death, following the removal of the Mubarak regime, Basiony’s video installation Thirty Days of Running in Place became Egypt’s official entry to the fifty-fourth Venice Biennale, in 2011. The installation was produced in 2010 and included a series of videos that depicted a man (the artist) wrapped in a sealed suit, jogging in place for an hour every day for a month, collecting and visually projecting information about the movements of his body onto a screen. Although Basiony’s work wasn’t initially received as political, in Venice it was shown alongside video footage of him participating in the revolution, thereby adding a political overtone.

Art and the Faltering Uprisings

As the uprisings soured, the dangers artists faced from any number of adversaries overtook the other factors that contributed to their newfound boldness. As early as 2012, as the high hopes of the Egyptian revolution began to get more complicated—if not actually fade—the art scene began to lose some of its verve and focus. Artists became more calculated in their risks. In despair or disillusionment or fear, some turned away from direct action in politics completely.

An early example of the casualties of this changing mood is the effort of the Barjeel Art Foundation to acquire a revolution-themed neon work by Moataz Nasr, The People Want the Fall of the Regime. This phrase was made popular during the Egyptian uprising earlier in 2011, as people took to the streets demanding the downfall of the Mubarak government. In fact, this work was so controversial that no Egyptian shipping firm would agree to ship it to the Gulf. On June 6, 2012 we received the following email. I have removed references to the sender to protect the person’s identity.

Dear _____

I would like to update you on the status of Moataz Nasr Neon Light work.

I have deliberately halted the shipping of this long overdue artwork for a serious strategic reason—my safety.

The piece is very controversial at this time in Egypt to be shipped out through such channel to the Emirates. Our people at the airport have checked the water and advised us to either wait or to have someone take it as luggage while travelling. The statement written on it “El Shaab Yourid Iskat el Nezam” could be seen as me (name removed), an Egyptian citizen, as trying to incite revolt in the UAE. As you may know, the UAE are very important for Egypt—politically and economically.

So bear with us. If you do come in the near future, best you or Sultan take it on your flight.

After several tries, the work finally arrived in the Emirates in November 2013. In order to avoid customs officials discerning the content of the Arabic words that make up the phrase, they were put into four separate packages. The label on the packaging from Egypt read “LIGHTING PEICE” (sic).

The episode was a harbinger. Egyptian authorities still deeply feared free expression, though at this stage and in this instance they were more concerned about the artist’s effect on foreign relations. The shipper understood that the Egyptian government might find the content of the artwork objectionable in its own right, or they might desire to censor it in order to erase any implication of Egyptians exporting revolutionary ideas around the region. By 2016, Sisi’s Egypt was experiencing a wintry freeze of political artistic expression. In the post-2011 period, successive, short-lived Egyptian administrations caught in the maelstrom and consumed with crisis management paid no heed to artists, initially allowing for an unprecedented degree of openness and artistic expression. However, since the authorities largely control the levers of media in Egypt, they were able to filter or promote any artists depending on whether they considered them to be antagonistic or friendly to the government, such as denying them the opportunities to be featured on local television or newspapers. The state had lost a lot of ground with all the changes of the last two decades, in terms of technology, markets for art, and boldness on the part of the artists. But it still had some tricks up its sleeve, and with its involvement in media, its promotion of fear, and its intimidation of artists, it had quite a bit of power, perhaps more than artists at the time realized.

The State Tightens Its Vise

With the rise of Sisi, this trend has taken firmer hold day by day, to the point that some of the sheen has been taken from overtly revolutionary art. The romance of the so-called Arab Spring—a name that was hardly used in the countries where it supposedly occurred—means that revolutionary Egyptian artists could make a living selling their works abroad. The idea has proved noxious, however, and many revolutionary artists avoided any obvious commercial benefit from revolutionary themes. As the political tide turned, many artists abandoned the themes of 2011–12, some turning to more personal, abstract, or subtle subjects.

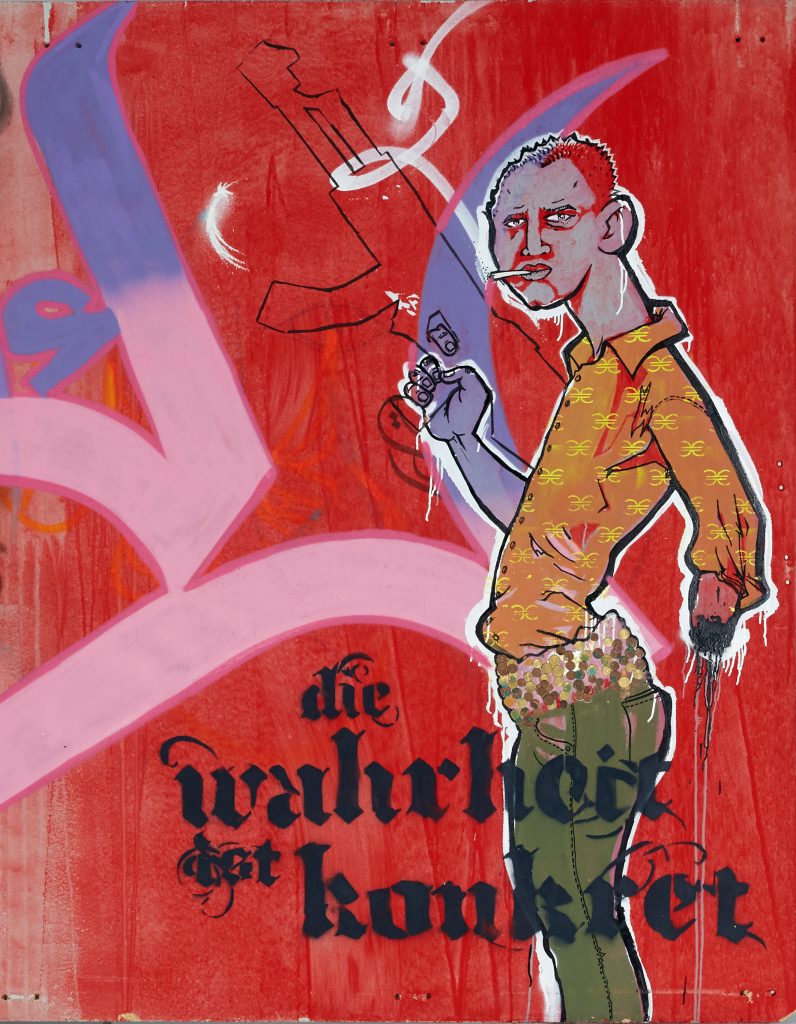

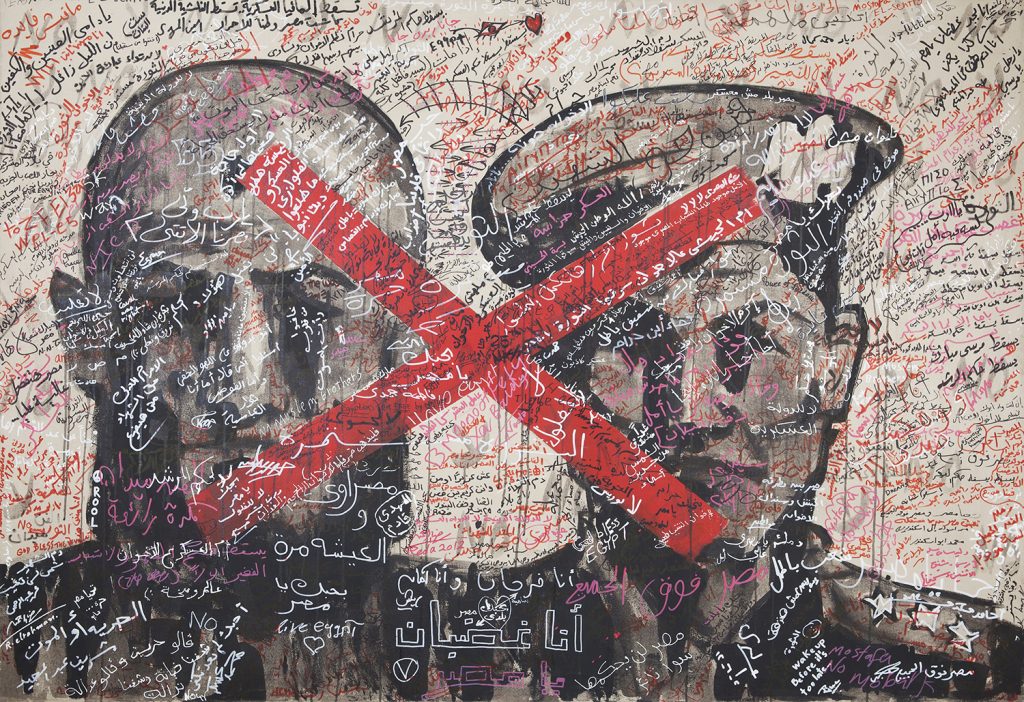

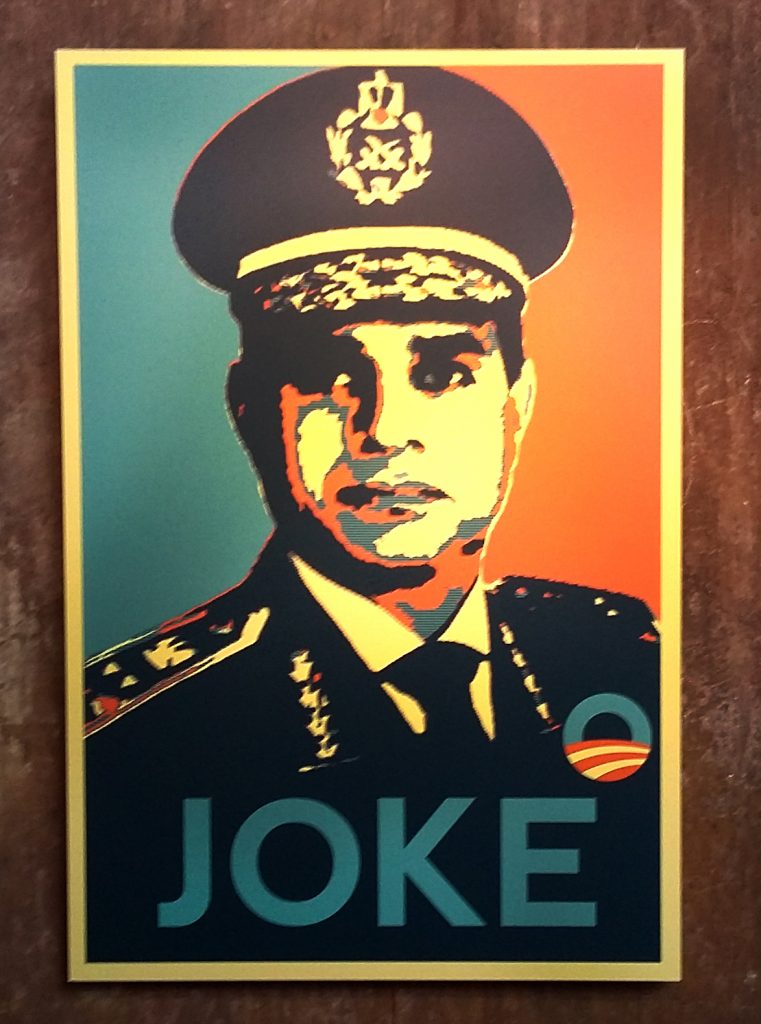

There have still been isolated instances of state criticism, and certain genres that have remained freer than others, such as editorial cartoons. JOKE, a 2013 poster mocking Sisi, by Egyptian graffiti artist Nazeer, was modeled on Shepard Fairey’s “HOPE” poster of Barack Obama. However, making fun of leaders can carry hefty fines or even a jail term. In 2015, twenty-two-year-old Amr Nohan was sentenced to three years in jail for sharing a photo of Sisi with Mickey Mouse ears on Facebook.

Sisi’s regime has attacked other art movements head-on. In December 2015, it shut Townhouse for two months along with the adjacent theatre and barred Aswany, the author, from public speaking.

The revolutionary fervor of artists, like other activists, has certainly been stifled. Some left art altogether. El Zeft, the artist who led the guerrilla muralists who painted the NDP headquarters, is himself an exemplary case. Five years after his daring graffiti assault, he has been drafted into the army, and is no longer active as an artist. Indeed, Sisi has made it very dangerous for anyone to attempt anything remotely resembling El Zeft’s 2012 feat. The NDP headquarters have been torn down, along with the graffiti, and the piece—which had a national impact at the time—is lost, and is now hardly mentioned in Egypt.

Other artists chose self-exile, such as Ganzeer, who now lives in Los Angeles. Ganzeer, the artist who made the famous poster Mask of Freedom (2011), has continued his provocations with Who’s Afraid of Art? (2014), which depicts Sisi in uniform, his face replaced by a rabbit staring from a television screen. The image was heavily shared on social media.

There is an inescapable feeling that something essential has been lost from the art world because of Sisi’s repression. The raucous, pure energy of 2011–13 is gone. Speaking to artists who still practice, one feels their disillusionment, and their creeping sense of guilt when they benefit from art that references a revolution that has all but failed.

And yet, many continue to create. This fact gets to the paradox at the heart of Arab art in the wake of the uprisings. Artists’ moods are as dismal as anyone’s. But as a critic who watches art closely and communicates with artists all the time, it’s impossible not to feel that something in Egyptian art went through an irreversible transformation during the uprisings, in terms of connecting directly with the masses. In those days of tumult artists got a vision of their power and possibilities. I believe that Sisi’s ham-handed suffocation of the art world is temporary. The government is less adept at propaganda than ever before, and artists have more tools than ever to spread dissenting messages. When the time is right, we will again see artists at the forefront of the next wave of change, whatever that may be. Their role has been diminished, but they continue to give a voice to civil society, despite the challenges of being blocked and silenced by state media.

Conclusion

Artists, far from being solely associated with the elite or even the ruling authorities in the Arab world, have shown that they identify with popular causes and even challenge elites. They have a long tradition of providing critiques of Arab regimes—with subtlety in times of great repression, with unabashed directness in times of tumult. With the symbols their media afford them, they have often been able to express the political desires of their societies’ peoples in a way that has been almost impossible through any other channels.

With the uprisings of 2011, Egyptian and Arab artists became far more deeply involved in politics—both in their art and by participating as demonstrators—and the lines between elite and popular art became blurry. But there was also continuity with the role that artists have filled since at least the early part of the twentieth century: then as now, they gave voice to the people when other means failed.

Even as the vise of authoritarian control is once more closing on artists, their role remains extremely important. Political art is one of the few outlets available, along with protesting, which is increasingly untenable. One could argue that, since art is far less disruptive than protesting in the streets, it is more of a pressure-releasing valve than a fomenter of change. As the examples in this essay have shown, however, the distinction between those two functions is oftentimes remarkably murky. Pondering which is the “real” role of art is more useful as an evaluation of a state policy than in understanding art’s actual significance.

Even when it is state-sponsored, art has been successful in reflecting popular sentiments ignored or repressed by Arab governments and artists, often reflecting the pulse of general society and acting as a bridge between the common man and the ears of those who will listen. As such, Arab governments such as Egypt’s, even if they were unwilling to become dramatically more democratic, might have treated art not only as a cultural asset but also as a measure of popular sentiment. Instead, most reacted to art with fear. And in the last two to three years, this fear has become more and more reactionary and stifling, especially in Egypt.

But artists keep the flame of independent thought alive in dark times. As the Arab uprisings seem to have faltered and lost their way, art still has potential and value—not just for its aesthetics but also for its relevance to material developments. Whether as a catalyst for change, a space for dreaming about possibilities, or a mirror of the fears and violence that have afflicted the region, art continues to serve as a space where Arabs rehearse and explore their political aspirations.

This article was originally published in The Century Foundation on May 16, 2017.