My most enduring memory of Dr Ramzi Dalloul (1935-2021) was at a dinner I hosted in my house in Dubai back in October 2014. Amongst the attendees were Egyptian collector and scholar Dr Hussam Rashwan along with Wendy Chamberlin, the president of the Washington DC based Middle East Institute, and young Syrian collector Khaled Jalanbo of The Jalanbo Collection.

My most enduring memory of Dr Ramzi Dalloul (1935-2021) was at a dinner I hosted in my house in Dubai back in October 2014. Amongst the attendees were Egyptian collector and scholar Dr Hussam Rashwan along with Wendy Chamberlin, the president of the Washington DC based Middle East Institute, and young Syrian collector Khaled Jalanbo of The Jalanbo Collection.

I then posed a question to Dr Dalloul asking him: “Can you tell us your philosophy behind collecting Arab art?” What I received was a 15 minute speech, parts of which are etched in my memory.

“Our culture, our civilisation is under threat from outside and from inside. ISIS has ransacked Iraq and Syria and destroyed priceless artefacts. Our children will no longer be able to experience these treasures. It is a battle for the minds of our children. Art can show them something they can be proud of, they can see the beauty of our culture and not only the negative news on TV. The best way now to unite the Arab people is not through politics but through culture.”

I remember wishing to interrupt him and reach out for my phone to record his words. Two years later—that speech still resonating in my mind—I invited him to speak at the closing of the exhibition Imperfect Chronology: Arab Art from the Modern to the Contemporary at the Whitechapel Gallery in October 2016. He spoke to me and a packed room in the 110 seat auditorium, along with at least 20 others standing, about Arab unity and social justice. He highlighted an “existential threat” that faces the Arab World that can, in his words, be confronted using a “cultural weapon.” The region, including its religious and political leaders he argued, failed to adequately face threats such as ISIS. Dr Dalloul’s response to such failures was to resort to the “brilliant works of art” that the Arab World has produced over the past 120 years and to bring them “all together to express the cumulative production of the Arab nation and the Arab peoples.”

The passing on of Dr Dalloul was a moment of reckoning for me. Although I only met him a dozen times or so, I felt a sense of cultural, political and ideological affinity with him. I genuinely feel I had lost an ally in my own cause of promoting Arab art. Dr Dalloul was amongst the last pan-Arabists of his generation with the understanding, as well as the willingness and financial clout, to invest in and attempt to resurrect the pan-Arab cultural movement that emerged in the mid 20th century, when Michel Aflaq called for a “revival of intrinsic humanity and creativity” of the Arab World. Back then, it was not uncommon to hear about the formation of regional cultural initiatives such as the General Union of Arab Plastic Artists in 1971, an Arab Biennial of 1974 in Baghdad, or the second Arab Biennial in Rabat in 1976 with its central theme of Palestine. Today, however, such pan-Arabist ideas are far fetched, and have even become a political taboo in some places. It is more common today to come across the growing interest in the art world of concepts such as the “Global South,” “globalism,” “MENASA” and “constellation modernism.” Few, if any, are left who would care about, let alone champion pan-Arab art.

I believed in Dr Dalloul’s project with all my heart and mind and I was happy to accommodate his requests. I recall receiving a call from him in April 2016, in which he asked me to refrain from bidding on a painting by Gibran Khalil Gibran that was coming up in auction in Europe. “It’s important that this work is in Lebanon. You see, I will be showing in my museum a sculpture I commissioned of Taha Hussein, and I can’t only show an Egyptian intellectual here in Lebanon without also showing a Lebanese intellectual. The Lebanese will not forgive me,” he ended jokingly. I did as promised, and refrained from bidding.

For Dr Dalloul, the collection was another manifestation of his long held ideology of pan-Arabism. If pan-Arabism for political leaders, like Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser, was inherently a project of political unity, for Dr Dalloul it was inherently a cultural project. Dr Dalloul even spoke of a plan that extends beyond a collection of modern and contemporary art, into a museum, and a cultural and performance centre. And like many grand projects, they are more often than not unachievable. Afterall, the first step towards realising such a goal is to imagine it; didn’t Gibran declare that “tomorrow is today’s dream”?

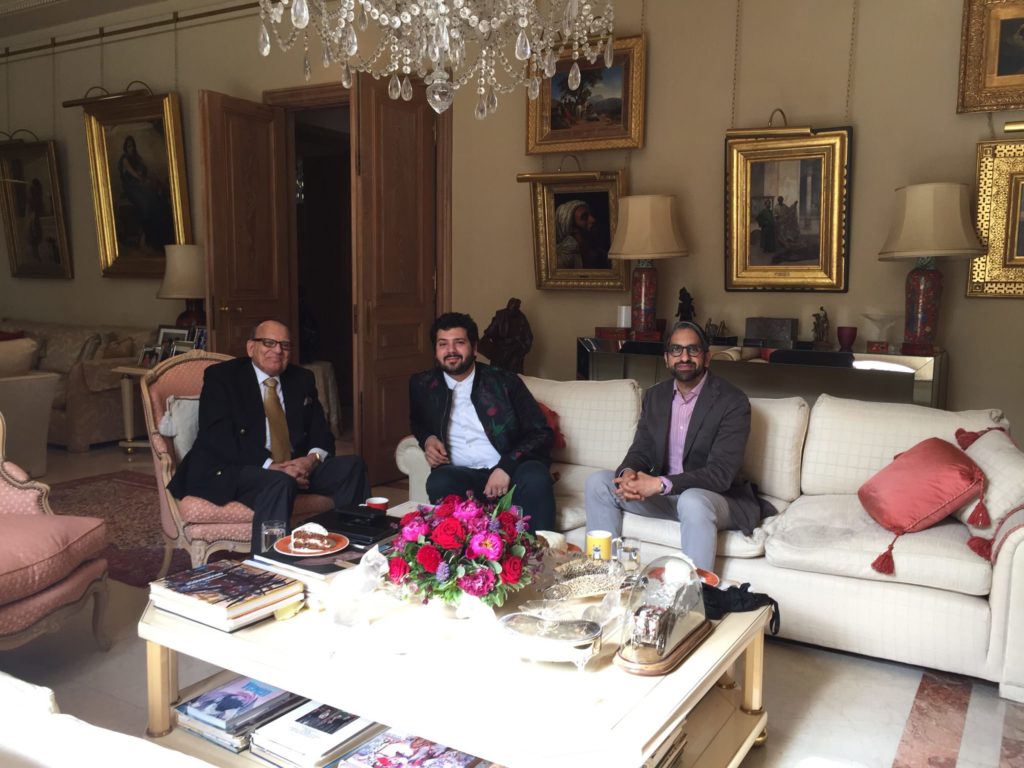

I did, of course, not always understand the philosophy or the methods behind his vision, and I may not have always agreed. I recall one evening, as we sat at Dr Dalloul’s house in London, he reached for a black plastic folder and showed me a printed photo of a painting of a seated woman by Egyptian modernist Hussein Bicar. He had a piece of paper folded into that page so he could find it with ease. “This is the work I want to acquire. I regard it as our Mona Lisa. Don’t you think it is beautiful?” I thought to myself, I am sure I have seen this work before. A few days later, I indeed remembered which collection held that work, and I reached out to them and asked what prompted them to offer works for sale. They said they were going through a rough period, and letting go of works from the collection as a last resort (it is in fact not uncommon for art institutions to sell works in order to raise funds). I told them to reach out to me in the future if they needed financial assistance and not sell their works. This artwork is currently not on the Dalloul Foundation’s website.

I regret not visiting Lebanon to see the collection together with Dr Dalloul, to have his energy reverberate in the room as he spoke about one work after another. The reason I was unable to, is because the UAE had barred its citizens from visiting Lebanon for the better part of the past decade. He once told me when we were at his home in London, “I don’t have the best modern Arab artworks here, it’s mostly the Orientalist paintings and a few Faeq Hassan works. You’ll have to come to Lebanon to see the collection.” I never did. Dr Dalloul, despite his advanced age, kept up with social media. Once at a gathering he told me “I have seen your facebook post in which you said people should reuse old buildings. It made me think about my museum. I will look for an unused building in Beirut and try to acquire it.” Sadly, Dr Dalloul died before he realised his project of building a museum in Lebanon to house a collection of over 4,000 works, amassed over several decades and named after himself and his late wife Saeda El Husseini Dalloul. Ultimately a Foundation was created by their son Dr Basel Dalloul in 2017 to manage and display the collection.

I repeatedly urged Dr Dalloul to exhibit the collection, to contact the Institut du Monde Arabe or the Sursock Museum and show some of his masterpieces, and although he loaned works from the collection, there was no exclusive presentation from the collection during his lifetime—a missed opportunity I feel. Part of my urging him was no doubt to satisfy a personal desire within me to experience in person an Arab art collection that is parallel to, though admittedly several times larger than Barjeel’s. Indeed Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art does offer such an opportunity, but geopolitics have rendered it inaccessible to me for years on end.

Dr Dalloul’s generosity has extended to numerous fields. He participated in a campaign to fund a library at Georgetown University, supported the Give Palestine Association along with Welfare Association (Taawon), co-funded the Edward Said Chair at Columbia University and sponsored the catalogue raisonné of Egyptian artist Mahmoud Said. However, despite all that he did, the media in the region was deafeningly silent about his passing. It seems our region’s obsession with politics is blinding us to anything else, including the passing on of one of the Arab World’s most significant cultural protagonists. There were a few references to his passing in the media, but nothing remotely fitting to his stature. One exception I found was Lebanese Arab nationalist intellectual and writer Ma’an Bashour who mourned Dr Dalloul, writing in Al Akhbar “Ramzi Dalloul wasn’t a regular person in his giving, however he did not like to appear [in public] and show off, in fact he was giving in silence, and working in silence, and achieving in silence, in all fields.”

This article was originally published in Mathqaf on April 6, 2021. A screenshot of this article can be downloaded here.