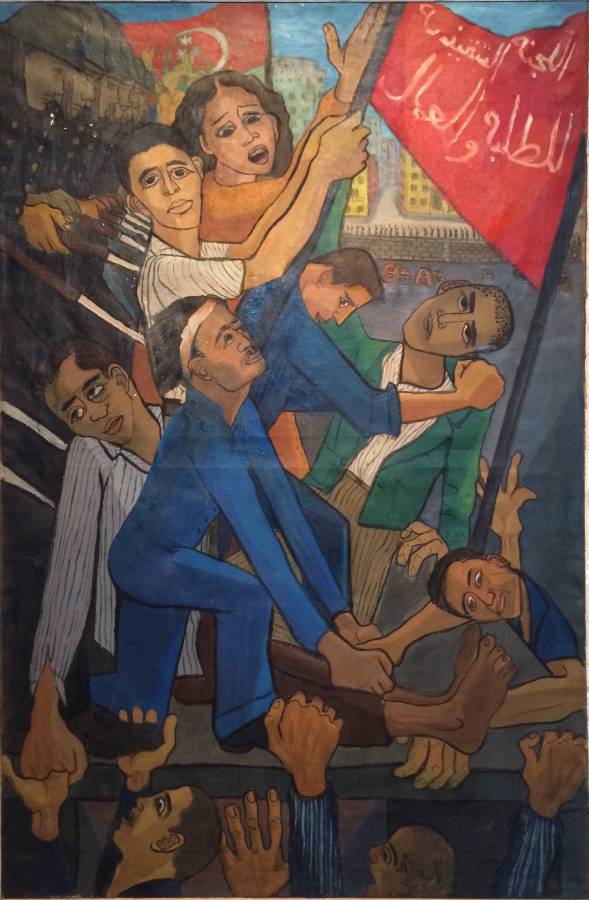

A group of workers and students are being pushed off a bridge by soldiers in helmets carrying bayonets. One soldier’s boot is pressing against the hands of a civilian, while another protester tries to help him hang on. A red flag fasted to sticks denoting socialism is blazoned with the words “Executive Committee of Students and Workers.” Gazbia Sirri’s painting Abbas Bridge (1955) is considered to be one of the earliest modern depictions of workers in a painting by a Egyptian artist.

The rise of liberation movements in the Arab World in the mid-20th century brought with them an array of complimenting works from the creative sector. Young men and women engaging in continuous protests required chants to sing and banners to carry, which were readily provided by poets and illustrators who often accompanied the protestors in the streets. An essential component of these liberation movements was the labour movement, which found eager partners and supporters within members of the arts community. This mass effort coincided with the strengthening, and in many cases assumption of power by socilaist and communist leaning groups that put workers’ rights at the forefront.

Sirri’s Abbas Bridge is based on real life events that took place in the industrial town of El-Mahalla el-Kubra in Egypt in 1947, and were then considered to be the largest protests of such nature in the country’s history. The government responded with force, and within five years the king was ousted in the 1952 Officers Coup in which “Egyptian workers played a catalyst political role” according to scholar Heba F. El-Shazli. In fact, under Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser, the image of workers took a drastic change. No longer were they hidden from view, or depicted in the background of artworks as passive bystanders.They were now celebrated front and centre in many works by Egyptian artists.

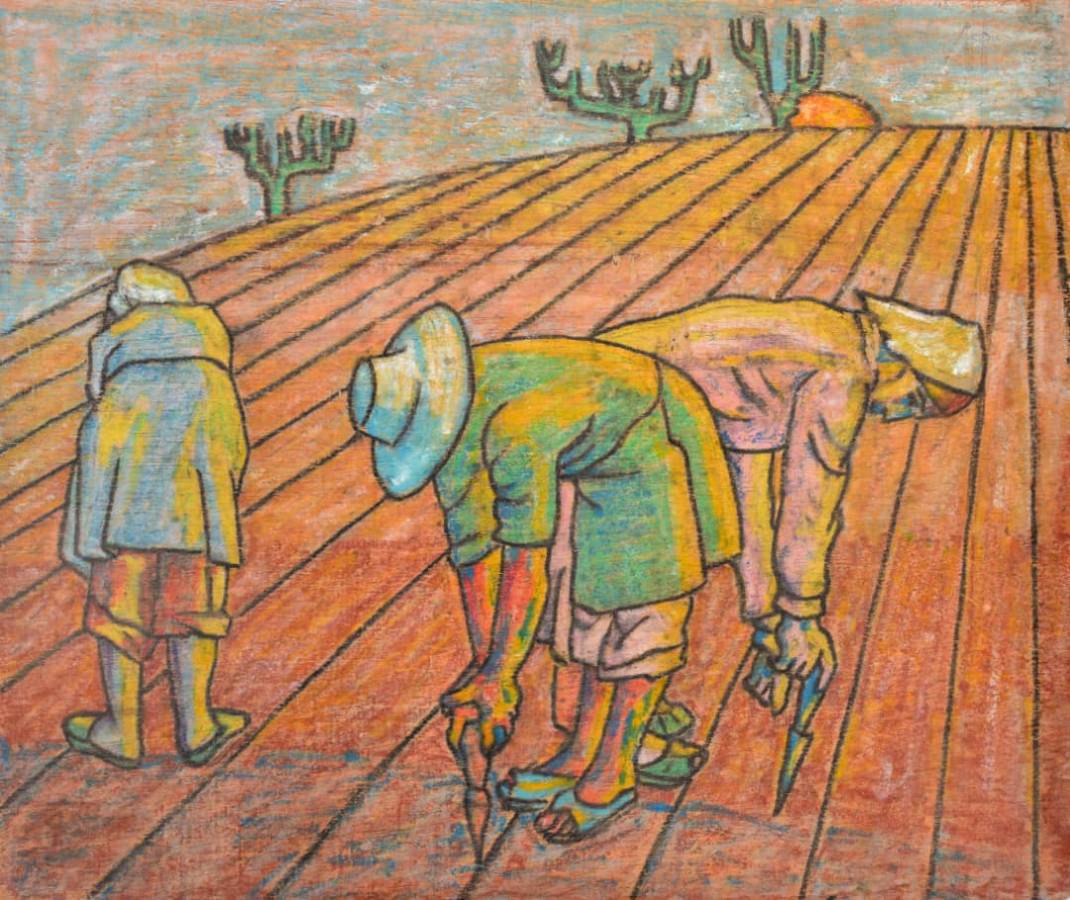

Perhaps few other artists depicted workers more often or with a greater sense of empathy than the Egyptian Hamed Ewais (1919-2011). In painting after painting, the ardent leftist portrayed fishermen, industrial workers, farmers, barbers and laundrymen as large, central figures dominating the composition. Ewais’ telling painting titles, which clearly dignified the proletariat, also betrayed his sympathies towards the working class. For example, following the Naksa—the Arab defeat in the Six-Day War of 1967—he portrayed a fellah (peasant) sporting a bandana and carrying a Soviet-made machine gun, titling it The Guardian of Life. This points to the high degree of respect that workers were shown by a generation of artists in Egypt in the 1950s and 1960s.

An equal champion of the working class was artist Inji Eflatoun (1924-1989) who was born into an upper middle class family in Cairo, and married communist prosecutor Hamdi Aboul Ela. Eflatoun’s activism for women and labour rights landed her a four plus year jail term. However, her spirit was relentless and she continued to depict workers in countless paintings, including The Builders (1952) and White Gold (1963) that comes from a series of cotton pickers that she painted in the 1960s. Similarly, Eflatoun’s contemporary Menhat Helmy (1925-2004) painted a composition called Procession to Work (1957), showing a group of male and female workers carrying tools, and marching behind a man holding a white pigeon—a popular symbol for peace. While professor of sculpture at the School of Fine Arts in Cairo Gamal Al Sagini’s (1917-1977) bronze piece titled Nasser (1960) depicts the Egyptian leader being supported by workers and peasants, representing different industries. The message is clear, workers amongst others, stand by Nasser and thus the president’s strength is derived from them.

Over in Iraq, Mahmoud Sabri’s (1927-2012) early works, including A Peasants Family (undated) and Builders (1957) exemplified his interest in the worker’s plight. As his career progressed, he continued to depict workers in paintings such as the Parsnip Seller (1950) and later, following his studies in Russia in the early 1960s with works like Family of Farmers. Like Ewais, Sabri gave titles to his works that reflected the tremendous respect he held for these labourers, which was evident in his portrayal of the execution of Salam Adel, the leader of the Iraqi Communict Party in 1963 that Sabri titled The Hero.

Sometimes the depiction workers can be a reflection of past events, as well as an omen of things to come—as in the case with He told us how it Happened (1957) by Iraq’s Kadhim Haydar (1932–1985) where a likely unemployed young man recounts a the events of the bloody crackdown against protesters at the orders of Prime Minister Nuri Pasha Al Said following the signing of the Baghdad Pact with Britain. Within a few months, the monarchy was toppled in the July 14 Revolution. Another major work by Kadhim Haydar is The Hands (1956), which depicts a group of impressively built male workers as well as a child, and which was shown in the historic exhibition of the Iraqi Artists Society held at the Royal Olympic Club in Baghdad under the patronage of King Faisal II in 1957.

Syria’s Leila Nseir (b.1941) put women front and centre in all her works, including a rare depiction of a woman martyr in her work The Nation (1978) being carried by a group of women and men. When it came to workers, Nseir depicted women as farmers in a field at dawn and close up portraits of women and men holding farming tools. Palestinian artist Vera Tamari (b.1945) also portrayed Palestinian Women at Work (1979), a ceramic relief as part of a series of works showing working class women, while Tunisia’s Safia Farhat (1924–2004) who is credited with revolutionsing arts education in Tunis’ Institute of Fine Arts depicted fishermen and labourers in numerous works. Farhat’s work both as an artist and as an educator, went hand in hand with her socialist politician husband Abdallah Farhat’s activism in the liberation movement of the North African state. This phenomenon is repeated in Palestine, where art movements are often inseparable from the liberation movement, and the depiction of workers becomes a central theme, in posters such as Arms of the Workers Protect the Revolution published in 1986 by the Palestine Martyrs Works Society (unknown artist).

Numerous Gulf artists who studied in Egypt also took to portraying workers, including Kuwait’s Abdullah Al Qassar (1941- 2003) who painted a scene of shipbuilders in Luxor Port (1964). The discovery of oil in the Gulf also propelled a number of artists to depict labourers, in works like Saudi’s Abdul Halim Al Radwi’s (1939-2006) Extraction of Oil (1965) which was turned into a postcard by Saudi Aramco, and Oil Exploration (1953) by Bahrain’s Abdullah Al Muharraqi (b. 1939). Furthermore, some Gulf artists have attempted to depict Asian labourers to whom these states’ economic prosperity owes a great deal. This was the case with Qatari Faraj Daham’s (b. 1956) Truck and Workers (2011) and more recently, with Emirati Asma Khoory’s (b. 1994) installation Look Beyond Them (2018) which offers an audio-visual diary of South Asian blue collar workers who are rarely if ever present or represented in the elite art scene in the Gulf.

Almost coming full circle from the mid 20th century, and recalling what one journalist called the “iconography of the 1940s” is a 2017 concrete relief work by Morocco’s Mustapha Akrim (b. 1981). The 200 cm diameter work titled Tools includes depictions of a shovel, saw, hammer, pliers, screw driver, mallet and a pickaxe, amongst other various instruments as a way to memorialise the unseen workers who are often hidden from society, especially in wealthier communities. Starting in the 1980s, Morocco embarked on major economic reforms supported by the IMF (International Monetary Fund) and World Bank, including privatisation programs that some argue have come at the expense of the working class.

Since at least the 1950s, Arab artists depicted workers in paintings, sculptures, posters and more recently, in new media and installations. In most instances, Arab artists depicted women and men side by side, performing the same tasks and protesting for the same goals and causes. Workers from different industries were not only painted as central figures, they were also depicted with dignity. Over the past three quarters of a century workers propelled social, economic and political change throughout the Arab world, however in recent years, more often than not they find themselves holding the short end of the stick.

This article was originally published in Raseef22 on June 27, 2020. A screenshot of this article can be downloaded here.