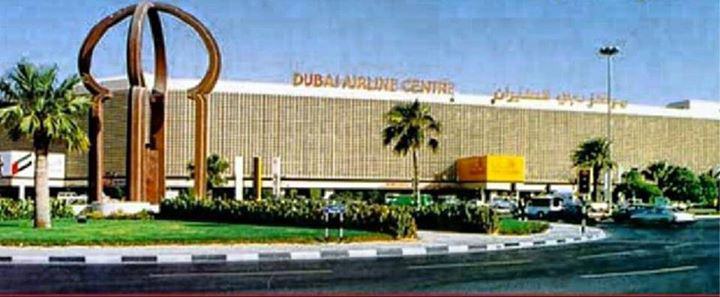

Anchored on the north-west side of Dubai’s Sheikh Zayed high-rise expressway is arguably one of its architectural jewels. A four decade old building that has hosted Dubai Petroleum’s headquarters since 1978. In 2009 this building was threatened by a new developer that was taking over the Satwa area to construct high-rise office blocks. A global financial crisis would have it otherwise and had stopped this tragic step from occurring. The Dubai Petroleum’s HQ must be preserved for the future of this country when it is vacated, and what way to better honour a building that has literally fueled the development of Dubai into a global city than turn it into a public institution, an art museum for the people.

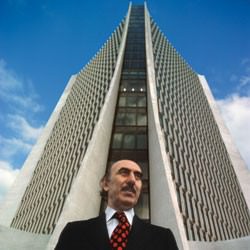

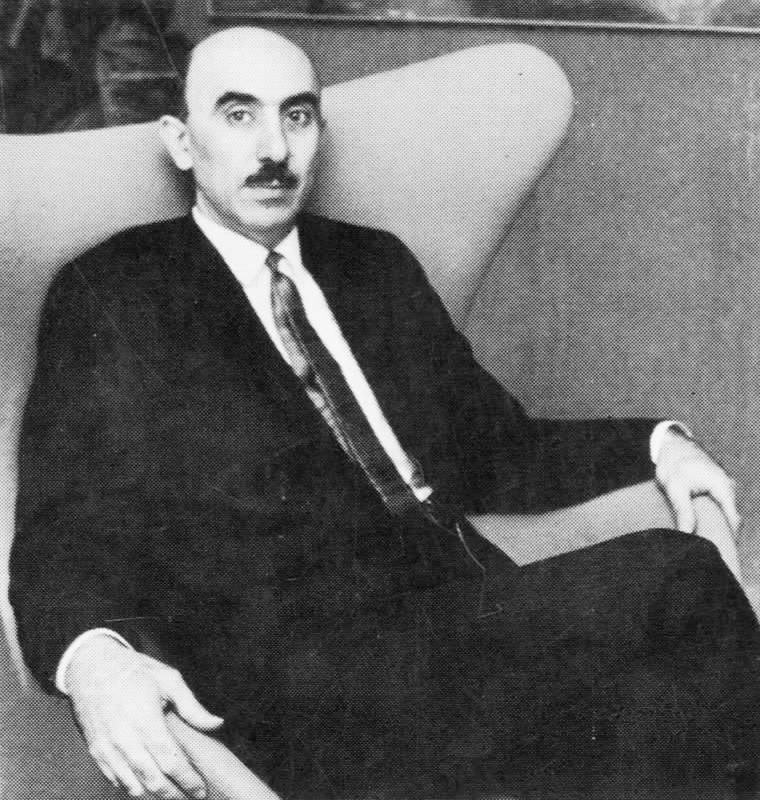

This 1978 four-storey building was designed by none other than Victor Hanna Bisharat (1920–1996), possibly the most famous Arab American architect that ever lived. Mr Bisharat (sometimes spelt Bishara) was born in as-Salt, Jordan and passed away in the US in 1996 (read The New York Times obituary here). He was responsible for various projects that literally altered the skyline of Stamford, Connecticut in the US and was hand picked to help design the world’s greatest entertainment park, Disneyland in Anaheim, California. Bisharat first left Jordan to study at the American University in Beirut, Lebanon and then attended the University of California at Berkeley.

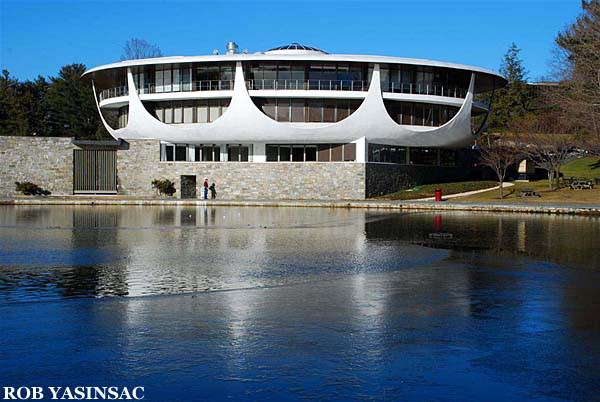

High Ridge Office Park in Stamford, CT. Photo by by Rob Yasinsac. Source: Hudson Valley Ruins.

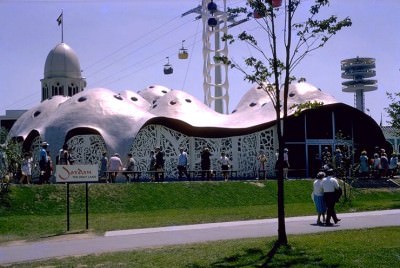

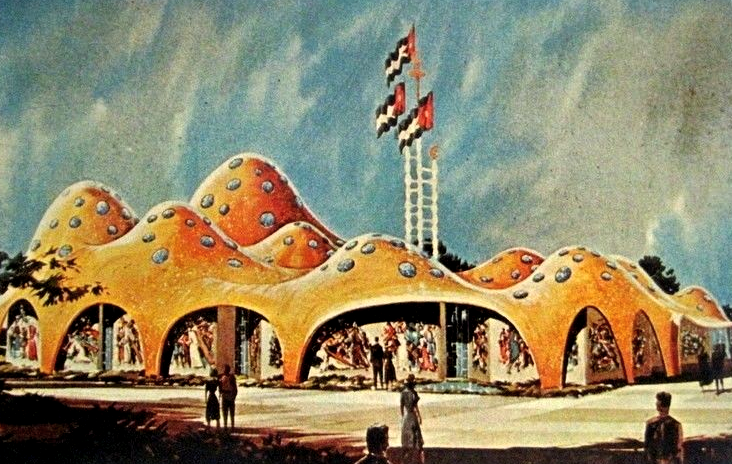

Bisharat’s projects were renowned in both the Middle East and in the United States. His architectuture was a bridge of cultural understanding for US audiences. While living in Pasadena, California he sketched the Pavilion of Jordan at the New York World’s Fair in 1964/65 before designing the UFO-like glass and white concrete office block in High Ridge Park and the GTE Corporation, formerly General Telephone & Electric Corporation in Stamford, Connecticut.

An Associated Press report by Samuel Koo from November 21 1974 states that he was born in Jerusalem, Palestine. The report also recounts an encounter Bisharat had with legendary architect Frank Lloyd Wright who met the young Arab-American while he was still a student at Berkley. Wright had apparently told Bishara, “Victor, if you hadn’t come to America, you would have been spared the agony of looking at it.”

The Pavilion of Jordan at the New York World Fair 1964/65. Photo by Mike Kraus. Source: NYWF64.

Amongst Bishara’s other structures in the region is the Koujak-Jaber Building in Beirut also known as the “Gruyere” building, the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Jordan and according to AP journlaist Koo projects in Kuwait, Qatar and Sharjah which I have not been able to locate as of yet.

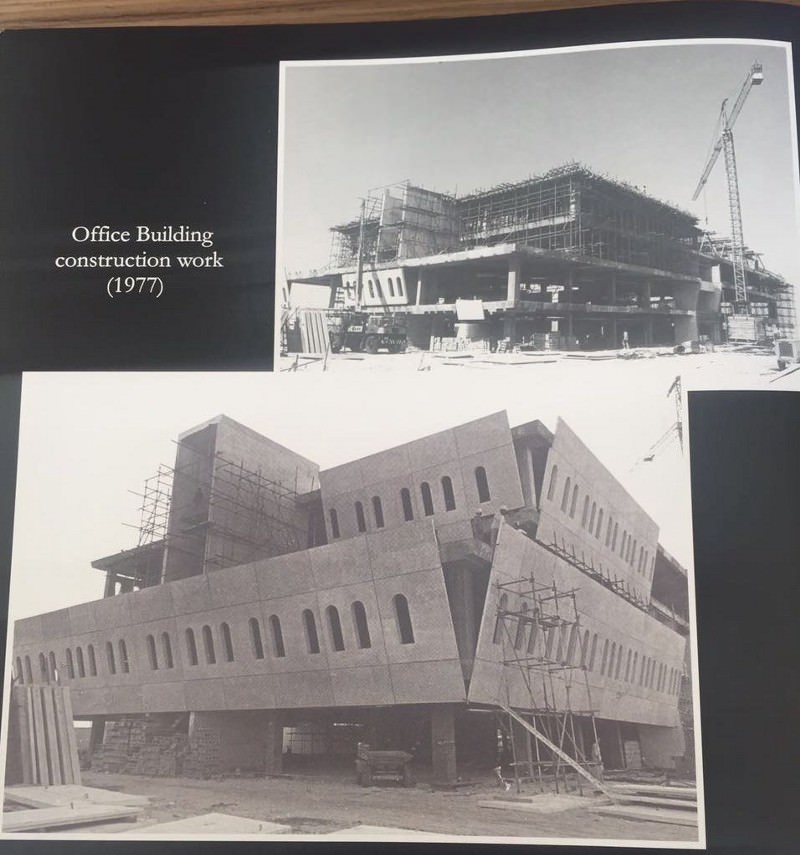

In 2014 the Dubai Petroleum building was one of the featured projects in the National Pavilion of the United Arab Emirates at the 14th Venice Architecture Biennale. Following exhaustive research by Curator Michele Bambling and Architect and Head of Research Adina Hempel more information about the building emerged. According to an interview they conducted with Yusef Shalabi, the director of projects at Al Habtoor Group in Dubai which constructed the building in the mid-1970s, the building was in fact commissioned for US energy giant ConocoPhillips which had operated an offshore oil and natural gas fields concession in Dubai since 1961. The Houston-based ConocoPhillips was aware of the work of Bisharat designing large headquarter structures including the GTE Headquarters in Stamford, Connecticut and invited him to Dubai to design their new office building which was then taken over by Dubai Petroleum.

Back in 2008, I read with mixed emotions how Dubai planned to build a 50-billion dirham art museum and district on the creek. That futuristic design was conceived by Dutch architects UNStudio whose other designs include the Mercedes-Benz Museum in Stuttgart, Germany. The proposed museum would have a building surface of 41,200m2, and was inspired by the dhow, a wooden ship common in the Arabian Gulf region. Comissioned by Dubai Porperties, the musuem would cost US$333 million (£255 million in 2008).

Rather than building from scratch Dubai would do well to learn from the experiences of other global cities that have renovated older buildings and turned them into national institutions. In London for instance, the Tate Modern museum was a former oil-fired power station and the grand structure of the Musée d’Orsay in Paris’ left bank housed a train station for decades.

Closer to home, Kuwait’s century old Al Sharqiya School serves today as one of three permanent art museums in the Gulf while Sharjah inaugurated the first Islamic Civilisations Museum in the region in 2008 in a magnificent converted souq originally designed by Edward Mansfield of Halcrow. Qatar’s Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art was originally built as a school and later transformed into an art museum by French architect Jean-François Bodin who recently completed the rennovation of the Musée Picasso in Paris.

Dubai need not reinvent the wheel, not with so many beautiful buildings that can be reenergized to serve more generations of this country. When I first published a version of this article in The National in 2010 I was invited to meet a senior official in Dubai who told me “I don’t promise you it will be turned into a museum but I promise it will not be demolished.” I was glad to know that she had taken an interest in the preservation of this important building that was later featured at the UAE Pavilion in Venice. Even years later when people ask me about which of my articles I feel had the greatest impact I immediately think of this incident.

Sadly, we previously lost other fascinating structures in Dubai to “modernisation”; think of the old Dnata head office in Deira and how its intricate beehive structure is today so tragically hidden in glass. At one point in time I honestly hoped no one would suggest covering the World Trade Centre tower in top-to-bottom sun-reflecting glass as is currently happening to the Wilson apartments building on the other side of the Dubai World Trade Centre roundabout. In 2009 I had the pleasure of visiting Dubai Petroleum’s head office and realised that its location, size and structure are a perfect setting for an art museum. Additionally over the past few years the area has also welcomed many residents and tourists thanks to major projects like City Walk which sits on the other side of the street.

I day dreamed as I walked through the Dubai Petroleum building during my visit and fantasied about the possibilities. The main structure houses a serenely enclosed courtyard ideal for the permanent collection of Middle Eastern art that Dubai planned for in the 50 billion-dirham project, and it won’t cost a fraction of that. The smaller east wing section can house exclusively Emirati or young artists from across the region and an annex building completed 20 years ago can act as a site for temporary exhibitions. Finally, the beautiful surrounding open spaces around the main structure can host a sculpture garden. Almost seven years on from that visit I still day dream about this building as though I never left.

We will be sending the right message by preserving this building; that Dubai is as much about honouring the past as it is about seeking a better future for its inhabitants. That culture is part of the city’s fabric and is nestled between the Sheikh Zayed Road, Burj Khalifa and Jumeirah. This is our opportunity to convert an older structure that has served the city so well and is designed by a world class architect and start approaching regional art collectors to adopt rooms in their names to house permanently or on a long term loan part of their own art collections.

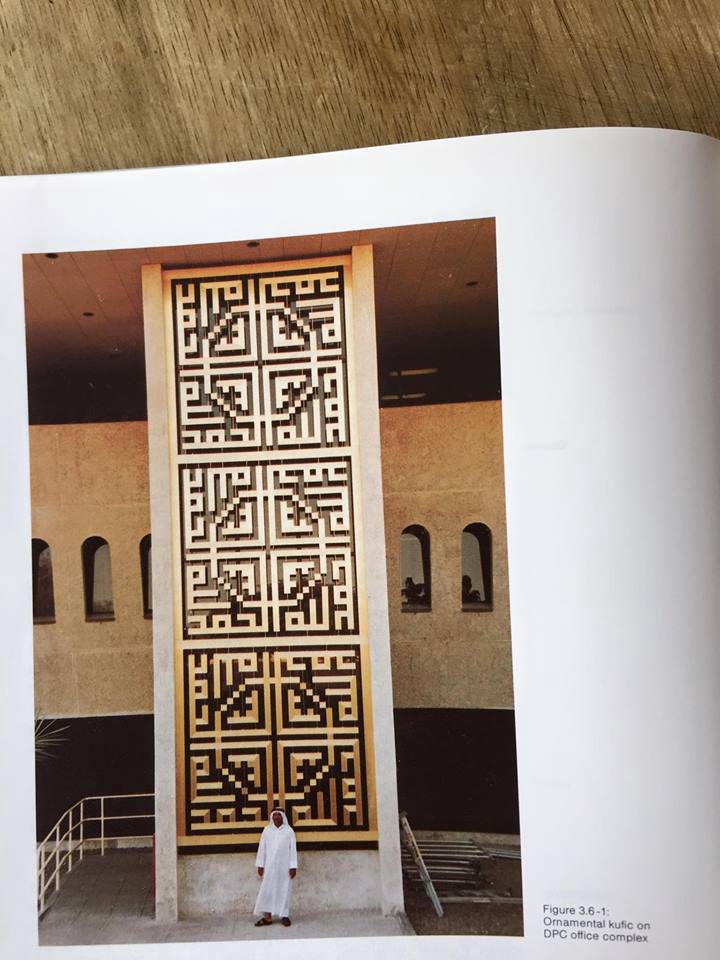

Video art, photography, paintings, etchings, sculpture and animation can all be accommodated in this building. I have been inside, and I have seen the light, literally. It shines through 15 hexagonal stars on the roof of the main building flooding the lobby floor garden with light. This building is ideal with open spaces and viewing halls as its many offices are separated by easily removable plywood that when cleared will free the vast rooms to reveal a perfect art gallery. The ornamental Kufic golden script above the building’s entrance and on the sides outside read “Praise be to God” is in itself a work of art.

Dubai can count on the numerous investors and bankers in addition to the art collectors, galleries and artists it has so very well served in the past decades not to hold back with their art collections and to share them with the public by adopting rooms or sections in their names. It need not cost 50 billion dirhams, heck; it need not cost 50 million dirhams. The building is more or less ready, preserving it exactly the way it is will be the best way to honour art and culture, honour history and ultimately honour Dubai, this beautiful city that we all love.

This article was originally published in Medium on August 23, 2016. A version of this article was published in The National on January 3, 2010. A screenshot of this article can be downloaded here.